Wounded Healers as Agents of Change: A Comparative Study on Stress and Work Satisfaction of Nepali Accompaniers {under peer review}

Research article

Yubaraj Adhikari, MHPSS Delegate, Syria Delegation, ICRC, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0587-9726

Pranab Dahal, PhD, Researcher, Linnaeus University, Sweden, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7399-9829

Bhava Poudyal, MHPSS Regional Advisor, ICRC, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5573-8799

Aims/objectives: The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) initiated a program in Nepal in 2010 to assist Families of Missing Persons (FoMPs). The program, which aimed to provide emotional and psychological support, recruited many FoMPs themselves as “accompaniers” (psychosocial service providers) to function as agents of change. This study digs into retrospective data of accompaniers’ psychological status to see if accompaniers from the FoMPs experienced elevated stress compared to their peers who were non-relatives of the Missing. The study also compared their personal growth, meaningfulness of work, and work satisfaction as lay counselors.

Methods: The purpose of the study was to evaluate and compare the level of stress of the two groups of accompaniers: those who were not related to the missing persons (n=39) and those who were (n=26). The study retrospectively compared the data of two groups using mixed methods, applying quantitative and qualitative methods. A locally developed 13-question self-administered perceived-impact scale covering five domains – negative effects of work, meaningfulness of their work, personal growth, level of supervision, and overall satisfaction with work - was used to gather the quantitative data. Individual interviews (five), and focused group discussions (FGDs, seven) were also employed to gather qualitative data from the respondents. The ethical clearance and data analysis procedures adhered to scientific protocols.

Results: The study found that two-thirds of respondents (n= 65) from both FoMPs accompaniers and non-FoMPs accompaniers disagreed that their work was very stressful. One-third of both groups expressed that their stress was initially increased due to the narratives of personal loss, uncertain life circumstances of FoMPs, and economic hardships. Non-FoMPs accompaniers experienced stress due to their lack of exposure to families affected by the conflict, while for the FoMPs, it was similar stories that triggered their loss. The program was also a source of company, social recognition, and social support, with access to opportunities. Recruitment of FoMPs accompaniers helped build rapport with target communities. The acceptance and the welcome by the families helped accompaniers in their work, more so for FoMPs accompaniers. Both groups of individuals developed a repertoire that included problem-focused coping strategies and emotion-focused coping techniques to ease negative emotions. The methods employed by both groups were sharing feelings, spending time with friends and family, reading, and distraction. Over 90% of accompaniers in both cohorts expressed personal growth (96% FoMPs and 95% non-FoMPs) and their work as meaningful (91% FoMPs and 94% Non-FoMPs). 87% of accompaniers from FoMPs and 95% of accompaniers from non-FoMPs cohorts shared overall satisfaction working as an accompanier.

Conclusion: The study findings showed that over two-thirds of individuals who served as accompaniers from FoMPs or Non-FoMPs did not suffer from severe stress or re-traumatization. Accompaniers, involved in this study, found hope, dignity, identity, opportunities, and pride due to their service. This study found that victims can be trained and supervised to function as agents of change for service recipients and themselves.

Keywords: Comparative study, Accompaniers, Stress, Coping, Wounded healers, Nepal

Introduction/Background

In 2010, the ICRC initiated a comprehensive psychosocial support program called “Hateymalo” Accompaniment Program (HAP) to mitigate the debilitating consequences of the uncertainty induced by the disappearances of loved ones at the individual, family, and social levels. This “Hateymalo” (holding hands) effort aimed to restore resilience by mobilizing resources available at the local and district levels. The program became a driving force in addressing the multi-faceted needs of FoMPs and restoring the well-being of both individuals and families by enhancing their functionality at the individual, family, and community levels.

The Hateymalo intervention reflected the ICRC’s philosophy of accompaniment. It was a novel approach for the ICRC’s psychosocial work that used peer support from FoMPs, in addition to other paraprofessionals from the community. The program mobilized Nepali psychologists, counselors, and paraprofessionals, an approach which, instead of directly replicating Western MHPSS approaches, respected and nurtured a community-driven, bottom-up, and culturally relevant approach. 124 accompaniers and 30 psychosocial counselors were the front-line service providers for 7,965 family members of missing persons residing in 46 districts of Nepal. A total of 47% of the accompaniers (58 out of 124) were recruited from FoMPs (ICRC, 2016).

This paper argues that actively recruiting, thoughtfully training, and rigorously supervising individuals with lived experience of significant personal adversity due to having a loved one missing, in the context of the conflict in Nepal, represents a viable, culturally resonant, and highly effective approach within LMIC task-shifting initiatives. Such individuals often possess an inherent understanding of the socio-cultural context of distress, enabling them to build trust and rapport more readily than external professionals (Miller & Baldwin, 2000). Their shared lived experience can foster an unparalleled level of empathy and relatability, helping to dismantle stigma and normalise help-seeking behaviours within their communities (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012).

Literature Review

The global burden of mental health conditions represents one of the most pressing public health challenges of our time, contributing significantly to disability, mortality, and economic loss worldwide (Whiteford et al., 2013). This crisis is particularly acute in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), where over 75% of individuals with mental, neurological, and substance use disorders receive no care (World Health Organization, 2022; Poudyal & Adhikari, 2022). Barriers to access are multifaceted, including profound shortages of specialised mental health professionals, pervasive stigma, lack of funding, and significant geographical and cultural distances between services and populations in need (Patel et al., 2018). In response to these systemic limitations, humanitarian agencies and national health systems in LMICs have increasingly embraced "task-shifting" as a vital strategy (Poudyal & Adhikari, 2022). This involves the training and supervision of non-specialist, often lay, health workers to deliver mental health interventions, thereby expanding the reach of essential care where professional expertise is scarce (World Health Organization, 2008; Rathod et al., 2017). While effective in bridging service gaps, the success of task-shifting hinges critically on the ability to recruit and prepare frontline helpers who can authentically connect with and effectively support individuals facing complex psychological distress, often exacerbated by socio-economic adversity, conflict, or displacement.

It is within this context of urgent need and innovative delivery models that the ancient archetype of the "wounded healer" gains contemporary relevance. Originating from the Greek myth of Chiron—the wise centaur who, despite his own incurable wound, became a renowned teacher and healer—and further elaborated by Carl Jung (1951 and 1966), this concept posits that an individual’s personal experience with suffering can paradoxically become a wellspring of therapeutic wisdom and empathy (Sedgwick, 1994). Jung famously asserted that "only the wounded physician heals," suggesting that effective therapeutic engagement often requires the practitioner to have personally traversed, and consciously integrated, aspects of their own psychological pain (Jung, 1929 and 1966, as cited in Sedgwick, 1994, p. 1). This perspective moves beyond viewing personal struggle as a disqualifier, reframing it as a potential asset for fostering deeper understanding and connection within the helping relationship.

The article will delve into the psychological underpinnings of the wounded healer, exploring how integrated personal suffering can enhance crucial therapeutic qualities such as empathy, authenticity, and the strength of the therapeutic alliance (Ardito & Rabellino, 2011; Kolden et al., 2011). It will also critically examine the inherent risks and "shadow side" of this, including the potential for detrimental effects, and professional burnout, issues that are particularly pertinent in high-stress, resource-constrained LMIC environments (Guggenbühl-Craig, 1971; Hayes et al., 2018; Figley, 2013; Adhikari, 2018).

Empowerment through Helping

The helper-therapy principle suggests that helping others can enhance one’s own recovery and self-worth (Hunter, 2021; James et al., 2012). In post-earthquake Haiti, lay mental health workers—many of whom were survivors—reported increased agency, dignity, and psychosocial stability after undergoing brief training and contributing to community mental health support (James et al., 2012). Similarly, in the Nepalese context, MHPSS professionals who worked with disaster victims reported a complex interaction of compassion satisfaction and emotional exhaustion (Adhikari, 2020). Survivors-turned-helpers were often intrinsically motivated by empathy and solidarity.

Vicarious Resilience and Growth

Rather than only focusing on the costs of trauma exposure, recent studies explore vicarious resilience—the emotional and psychological growth experienced by helpers who witness resilience in others (McGlinchey & Killian, 2025; Dimitriadis, 2025). For some, this transformation reframes their trauma into a source of strength. Dimitriadis (2025) found that refugee care workers with personal trauma histories benefited from reflective supervision and collective psychosocial spaces. Their capacity to identify with clients often deepened relational and therapeutic alliance.

Risks and Ethical Concerns

Despite these positives, risks do remain. Repeated exposure to others’ suffering can result in secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue (Kraybill, 2015; Izquierdo et al., 2018). The UNHCR and other global actors have documented how insufficient psychosocial support for aid workers, including those with trauma histories, leads to burnout and emotional disengagement (Welton-Mitchell, 2013). Cherepanov (2018) cautions that assigning survivors to helper roles without adequate boundaries or training may cause psychological harm and reinforce exploitative dynamics under the guise of empowerment.

Structural and Organisational Support

Organisational strategies that promote well-being—such as reflective debriefing, peer supervision, and manageable caseloads—are essential (Li et al., 2024; Adhikari, 2018). Structured training programs, like those developed for lay workers in Haiti, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, demonstrate how proper scaffolding can make survivor-helper roles both effective and sustainable (James et al., 2012; Adhikari, 2020; Andersen et al, 2020). Literature converges on a nuanced understanding: helping can heal, but only within frameworks that prioritise boundaries, support, and ethical clarity.

When it comes to families of missing persons, research has shown that these wounded healers have been very effective in reducing symptoms of their peers in terms of anxiety, depression, somatic pain, and increasing the day-to-day functioning (Andersen et al, 2020; ICRC, 2016). However, the well-being of these wounded healers is understudied.

This paper presents an empirical investigation into the psychosocial well-being of "wounded healers"—defined in this context as “accompaniers” who have personally endured the profound suffering of ambiguous loss (Boss, 2002) due to having a family member missing during the conflict in Nepal. Their experiences are quantitatively and qualitatively compared with a counterpart group of "accompaniers" who, while also engaged in providing psychosocial support in the same context, had not undergone this specific form of loss. This comparative analysis aims to elucidate the unique challenges and resilient adaptations present within both groups, providing critical insights into the psychosocial well-being of individuals delivering mental health support in conflict-affected Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs).

Aim and Objective of the research

The study aimed to assess whether FoMPs accompaniers exhibited increased levels of stress due to their work as compared to accompaniers who were not related to missing persons. The study utilised locally developed self-reported questionnaires and qualitative feedback to differentiate between the psychological stresses and challenges faced by FoMPs’ accompaniers and those faced by non-FoMPs’ accompaniers. It also identified the coping mechanisms adopted by accompaniers and explored the supervision and support system for accompaniers.

Methodology

The study used both quantitative and qualitative methods to determine the nature and types of stresses, coping behaviours, and the overall psychosocial well-being of accompaniers. The study was conducted in four locations in Nepal, covering respondents from 21 districts.

Research methodology

The perceived–impact-scale questionnaire was developed locally, based on the literature review highlighted above and pre-tested. The required changes in word construction were identified during pre-testing and were adjusted for better comprehension before the questionnaire was administered to the 65 respondents. Structured focused group discussion and semi-structured interview guidelines were developed. Discussions with support group beneficiaries and families were informal.

Quantitative Method

The quantitative analysis consisted of a 13-question self-administered perceived-impact-scale questionnaire. The questions were segregated into five domains: a) negative effects, b) meaningful work, c) personal growth, d) level of support received, and e) overall satisfaction in the role of accompaniers (see Table 1). The 13 questions used a Likert scale, providing respondents with five options (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, Agree, Strongly Agree) to choose from. The respondents were instructed to select the most fitting response. An additional last question was an open-ended one, which asked accompaniers to list three positive and three negative aspects of recruiting accompaniers from among FoMPs for future consideration.

Table 1. Perceived-impact-scale questionnaire

|

Theme |

Items |

|

Negative effect |

1. My tension (stress level) heavily increased when I worked for the Hateymalo program. |

|

2. Stories from FOM triggered my personal issues (story of loss) to a point where it intensely overwhelmed me. |

|

|

3. While trying to help families of Missing, I ended up suffering from compassion fatigue (fatigue due to emotional care). |

|

|

4. At some stage of my engagement in Hateymalo program, I wanted to quit my job because it was too difficult/stressful. |

|

|

Meaningful work |

5. I felt my work as an accompanier is/was meaningful to help families to move on with their lives. |

|

6. I felt my work as an accompanier is/was meaningful for me. |

|

|

Personal Growth |

7. After working as an accompanier, I was able to better support my family, bringing better family harmony. |

|

8. My engagement as an accompanier improved my social life (meeting others, going out, having people to share with) |

|

|

9. Through the Hateymalo program, I enhanced my skills in understanding my personal difficulties and in managing them |

|

|

10. After being an accompanier, I developed my confidence in identifying resources for a given problem and utilizing/mobilizing them |

|

|

Support received |

11. I received necessary support from my colleagues and superiors whenever needed while implementing the activities in the field. |

|

Overall Satisfaction |

12. I am happy that I worked as an accompanier for the Hateymalo program. |

|

13. Overall, I think I am a relatively happy and satisfied person. |

During the survey, 21 males (11 FoMPs and 10 non-FoMPs) and 44 females (15 FoMPs and 29 Non-FoMPs) completed the survey questionnaires.

Qualitative Method

A phenomenological study of accompaniers’ subjective views on stress, coping, and well-being employed a qualitative approach through focused group discussions (FGDs), and individual interviews. Of the total seven FGDs, two were conducted only with FoMPs and two only with non-FoMPs separately. The three mixed-group FGDs were used to triangulate the information.

Seven individual in-depth interviews were conducted with accompaniers, counsellors, and team leaders. They were intended to validate information provided in FGDs as well as to bring forth any issues that remained hidden during group discussions.

Data Analysis

The quantitative data collected using the Likert scale were cleaned, coded, tabulated and interpreted with % and numbers of responses in each item. For the simplicity of presentation, ratings of strongly agree and agree were merged and coded as agree, and neutral were kept neutral, and strongly disagree and disagree were combined as disagree. All results were tabulated and presented in % and compared between the responses from two groups - FoMPs accompaniers and non-FoMPs accompaniers. The qualitative data were obtained through recordings of FGDs, which were translated and transcribed after giving special codes to each speaker. Qualitative information was categorised during the analysis of raw data. The field notes of the interviews were critically examined to identify common themes. The positive and negative aspects of involving FoMPs as accompaniers, which the accompaniers themselves identified, were analysed using a content analysis method. Qualitative findings are exclusively embedded in the discussion section and interpreted to substantiate the quantitative results in this article with appropriate sub-themes derived through the literature review.

This research followed and reported based on the recommendations provided by by Leech and Onwuegbuzie (2010) in the guidelines for conducting and reporting mixed research in the field of counselling and beyond.

Results

The study found that out of 65 respondents, 68% of FoMPs’ accompaniers and 70% of non-FoMPs’ accompaniers disagreed that their work was very stressful. One-third of both groups expressed that their stress was initially increased due to narratives of personal loss, uncertain life circumstances of FoMPs, and economic hardships. Non-FoMPs accompaniers felt greater levels of stress initially because they had never been exposed to the experiences of FoMPs and were experiencing such pain for the first time. Having to listen to stories of trauma, loss that is ambiguous, isolation, societal prejudice, family disintegration, uncertainty, and distress was a major source of stress for non-FoMPs accompaniers, most of whom joined the programme as they would any other job, for employment, earning, and livelihood, without being aware of the possible work-related stresses. In contrast, FoMPs accompaniers had themselves undergone similar experiences and were coping, so exposure to FoMPs in and of itself had no significant effect on them. Most FoMPs accompaniers were motivated by a desire to serve and help, and had been aware of the possible accompanying stresses before they got involved.

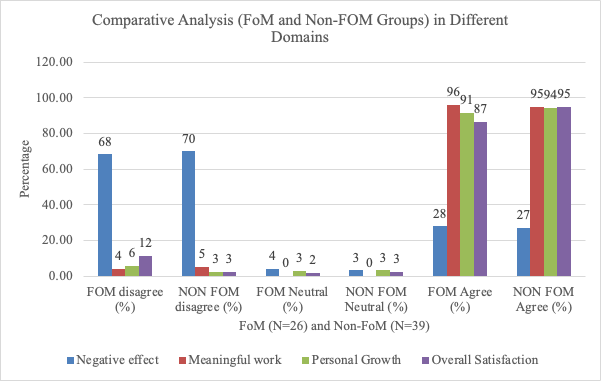

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows that over 90% of accompaniers in both cohorts expressed personal growth (96% FoMPs and 95% non-FoMPs), and their work as meaningful (91% FoMPs and 94% Non-FoMPs). 87% of accompaniers from FoMPs and 95% of accompaniers from non-FoMPs cohorts shared overall satisfaction working as an accompanier.

The program was perceived as a source of company, social recognition, and social support, with access to opportunities. Recruitment of FoMPs’ accompaniers helped build rapport with target communities. The acceptance and the welcome by the families helped accompaniers in their work, more so for FoMPs’ accompaniers. Both groups of individuals developed a repertoire that included problem-focused coping strategies and emotion-focused coping techniques to ease negative emotions. The methods employed by both groups were sharing feelings, spending time with friends and family, reading, and distraction.

Discussion with Qualitative Findings

This section analyses and supports the findings of the results derived from the quantitative survey explained earlier.

Psychological Stresses and Challenges Faced by Accompaniers

For one-third of FoMPs accompaniers who reported distress in the initial stage, the narratives of other families were a significant trigger of memories, as the following testimony indicates:

When families explain their problems and start crying, I am forced to think about my own missing family member, a remembrance which stresses me considerably. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R107)

During most of the sessions and training exercises, I thought a lot about my missing father. —Male, FoMPs accompanier, Chitwan (R205)

For the non-FoMPs accompaniers who expressed distress, it was due to the FoMPs’ stories of destitution and desperation. Listening to FoMPs’ stories of poverty, increased responsibilities due to the absence of a family member, and their helplessness allowed non-FoMPs accompaniers to understand their sufferings, but also increased their levels of stress.

I never even imagined people lived in so much pain. One elderly woman in my group had a missing son and took care of her nine-year-old grandson. It took me a while to get to know much about her, but I discovered that her husband had settled in a different location with his second wife and that her daughter-in-law had remarried and abandoned relations her son and mother-in-law. This feeble old woman was the only caretaker of the child, but she had no means to earn a living other than the mercy of passersby and a small plot of land on which she squatted. She farmed that land to produce a few meals. —Male non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R502)

The poverty of the families made me feel like crying. Seeing hungry and naked children living in a home without a roof used to make me break down completely. One family was very poor. They had literally nothing to survive on, but as a gesture of appreciation for my help, they would always offer me food. I used to lie, saying I had just eaten, because I knew that if I ate, then someone in the family would go hungry that day. —Female non-FoM accompanier, Nepalgunj (R902)

Exposure to situations of dire poverty and despair affected the accompaniers, who felt stress because they were unable to help FoMPs materially or financially. The psychological triggering of this stress, however, faded quickly, with continued exposure and the passage of time. The professional stress that resulted from the nature of the work, including travelling considerable distances to meet families, conducting support group meetings, reporting, and keeping records, affected FoMPs and non-FoMPs accompaniers equally. This stress was more pronounced during the initial phases, when accompaniers were first exposed to families and their problems during the household survey and other early programme activities.

The initial two or three months are painful for almost all accompaniers as they are exposed to the sea of pain of the families. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R507)

Initially, the programme was very stressful because I would relate the FoM’s stories of loss with my own. But now, because of the training and having been exposed to many families like mine, I feel that I can handle my personal stress effectively. —Female FoMPs, Chitwan (R605)

Some families, who had been disillusioned and disgruntled after incessant interviews by human rights organisations, authorities, and civil society groups, with no outcome or support, were initially not very welcoming to the accompaniers. This was a source of stress for the accompaniers.

The most common remark I got from families during the initial days was, ‘Why have you come to scar us again for a pain that was already healing?’—Male FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R106)

During the initial stage of the programme, most said that they were sick and tired of sharing their stories of loss. Some even provided false information. The unresponsiveness of FoMs and the false information I received during data collection were stressful moments for me. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Chitwan (R705)

Gender differences and the work-home balance were sources of stress for some female accompaniers. Most married female accompaniers had to manage both their personal and professional lives. When it was difficult to handle both, as it sometimes was, they experienced stress. Gender differences also caused significant stress for those female accompaniers who had to oversee fathers’ groups. Interestingly, no male accompanier reported experiencing a similar level of stress while managing mothers’ or wives’ support groups.

We women have the dual responsibility of managing our homes and our jobs. Managing both efficiently at all times is beyond our capacity, a fact which significantly influences our level of stress. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R203)]

Handling a fathers’ group was a serious challenge for me, one which created a great deal of stress. The fathers’ group members are politically very enlightened, and at times they ignored meeting protocol, preferring to pursue digressions about issues irrelevant to the group. I, as a woman, would be tolerant of their ways and would respect them because they were older. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Chitwan (R305)

The second phase of the programme with the FoMPs, which comprised conducting support group activities largely focused on sharing, coping together, networking, and the use of available services, was considered an easier phase.

Three accompaniers who left the programme midway cited personal reasons unrelated to stress for choosing not to continue. One quit for another job with more economic benefits and opportunities. Another had to leave because he had been charged with a criminal offence unrelated to his work for the programme. The third dropout quit because she moved from her working district to Kathmandu to continue her studies.

Personal Growth

Accompaniers from both cohorts expressed personal growth in different dimensions:

The programme has increased my self-confidence, so now I feel I can do anything anywhere and work with anyone. —Male non-FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R206)

My networking skills have improved immensely and developed, and I am able to utilise available resources as well. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R606)

I learned to look forward and forget my pain. Doing so has been significant for my personal and professional growth. —Male FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R306)

I don’t think I will ever do anything better than this in my life. The programme helped me help numerous families who were in desperate need. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R507)

FoMPs Versus Non-FoMPs Accompaniers

The differences between FoMPs and non-FoMPs accompaniers include both differences perceived by individual accompaniers and those perceived by the communities and families they serve. Rapport development between the beneficiaries and FoMPs accompaniers was quick because they shared similar pain and problems. Non-FoMPs accompaniers as well as beneficiaries themselves testify that a fast-developing bond is always guaranteed when an FoMPs accompanier visits a beneficiary family, but this is not always the case when it is a non-FoMPs accompanier. A few FoMPs felt that non-FoMPs accompaniers did not always understand their grievances and pain.

I feel we are closer to FoMPs as we share similar stories of pain. It is easier to share their personal stories and suffering with an FoMPs accompanier than a non-FoMPs accompanier. FoMPs feel that FoMPs accompaniers live the lives they live and therefore feel close. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R701)

Yes, I completely agree that families and groups are able to open up more to someone who bears similar losses. Even with us, when we share our loss, an immediate bond forms, building a relationship at a different level. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R201)

The level of trust that an FoMPs accompanier can establish and maintain is high. Most FoMPs and beneficiaries reported that they were more open with FoMPs than non-FoMPs accompaniers. They said that they felt more at ease initiating discussion on all sorts of issues since FoMPs’ accompaniers have undergone similar experiences to their own. This difference in trust alone underscores the importance of having wounded healers as frontline workers.

The presence of an FoMPs accompanier has great significance for FoMPs. I used to conduct sessions alone, but later on I teamed up with an FoMPs accompanier and found that the acceptance I received from the families was greater than when I was alone. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R206)

I feel that no matter how good I am at expressing concern and sharing pain, it always seems superficial as my feelings lack knowledge of real suffering. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R506)

Perception of the Positive and Negative Aspects of Involving FoMPs Accompaniers

In their self-determination theory of human motivation, Deci and Ryan (2008) conceptualise psychosocial well-being as some combination of positive affective states such as happiness (the hedonic perspective) and optimally effective functioning in individual and social life (the eudemonic perspective). Subjective well-being is a construct that reflects an individual’s appraisal of his or her life. Such appraisals may be cognitive (e.g. life satisfaction) or affective, in which case they consist of the pleasant or unpleasant emotions that individuals experience (e.g. happiness and depression). Subjective well-being incorporates positive factors and is not merely the absence of negative factors (Park, 2004).

An open-ended question asked respondents to list out three positive and three negative aspects of involving FoMPs accompaniers. An analysis of the themes revealed that, for FoM accompaniers, ‘personal stress reduction’, as mentioned by 39 respondents out of 65, was the major positive aspect. ‘Understanding issues more easily’ was outlined by 32 respondents, and 27 respondents mentioned ‘greater motivation and self-confidence.’ The top three reported negative aspects for involving FoM accompaniers, was outlined by 35, 33 and 28 respondents respectively, were the ‘difficulty in working with one’s own family’, ‘reminders of personal losses’, and ‘families’ mistaken belief that all FoMPs accompaniers, by virtue of their having experienced the disappearance of a loved one, are aware of all their problems. All positive and negative aspects outlined and listed by the respondents are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

|

Positive aspects |

Negative aspects |

|

Problem-solving |

Higher expectations from programme |

|

Resource identification |

Higher compassion fatigue |

|

Maintenance of cordial family relations |

Less time for own family |

|

Help for other families |

Persistent insecurity after termination of programme |

|

Warm welcome from families |

Less understanding of psychosocial issues |

|

Personal stress reduction |

A feeling of helplessness and increase in stress |

|

Greater motivation and self-confidence |

Personal family problems and disputes |

|

Good capability to advise |

Reminders of personal loss |

|

Provision of emotional support to FoMPs |

False assumption that an FoMPs accompanier is aware of all problems |

|

Networking abilities |

Reduction in trust if the FoMPs accompanier is from the opposite political camp (state vs. rebel) |

|

Greater sympathy |

False pride in being indispensable to the programme |

|

Working together with FoMPs for similar causes |

|

|

Easier understanding of issues |

|

|

More positivity from FoMPs as the presence of an FoMPs accompanier decreases their expectations |

Coping Mechanisms Developed by Accompaniers

Coping mechanisms are often influenced by hope and optimism to promote subjective well-being. Snyder (1999) defines coping as a response aimed at diminishing the physical, emotional and psychological burden that is linked to stressful life events and daily hassles. Similarly, Lazarus (1993) defines it as constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding a person’s resources.

Coping is a process of regulating emotional reactions to external factors. As such, it has been defined as a subset of all those self-regulatory processes that take place in stressful circumstances (Compas et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 1997; Skinner & Wellborn, 2019). When confronted with stress, individuals attempt not only to deal with emotional experience, expression, and physiological reactions but also to coordinate motor behaviour, attention, cognition, and reactions to social and physical environments (Compas et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 1997; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

The major coping mechanisms used by accompaniers were sharing their personal stories among themselves, with family members, and, most importantly, with supervisors. Most accompaniers reported that consultations with supervisors brought considerable relief. Another important coping mechanism was diverting their attention to other household and social matters.

They reported that the skills they learned during the training were another “very useful” method of coping, especially during real-time interactions with families in which family members expressed their emotions or were reluctant to participate. Even those family members who had not even come out from their houses to meet the accompaniers when they first arrived had later bonded so closely that they regularly phoned them for advice about even small matters and were very happy to share with them in general. Some family members said that they saw their missing member in the accompanier and started treating the accompanier as one of their own, a phenomenon called transference in psychological terms. This positive change in the behaviour of beneficiaries and being treated as part of the family in a collective society was reported to have compensated for all the hardships that FoMPs' accompaniers had to undergo in the initial phase of the programme.

Coping is more broadly seen as a combination of processes of action and of reaction to personal and external stimuli. The feeling of solidarity and the knowledge that there are other victims of disappearance helped to decrease stress levels among FoM accompaniers.

I felt that I was not alone in having undergone this traumatic experience. The bonds I developed with people like me who also had missing family members, and sharing our stories of suffering, also helped me overcome the stress I felt. —Female FoMPs accomapnier, Nepalgunj (R201)

The programme helped me meet young women whose husbands were missing, elderly mothers waiting for their sons, and young children whose fathers were missing. I lost my brother, but their sufferings were worse than mine. Working with them helped me enormously to console myself that my loss was nothing compared to theirs. —Female FoM accompanier, Nepalgunj (R801)

A re-focus on the “here and now” and away from only the ambiguous loss was seen.

How long can we carry stress in our heads? We have to let go and explore to find other, unseen happiness in our lives. This was the question I used to ask myself whenever I got stressed. I decided to go for happiness and move away from the stress. For me this approach worked well: positivity toward my life helped me reduce my stress levels and overcome the loss of having a family member disappear. —Female FoM accompanier, Nepalgunj (R801)

Personal care and management were another major source of energy to cope with stress, as was sharing issues with friends, family members, and colleagues.

Sleep and self-consolation were the major ways I overcame stress. I also used to share my problems with superiors and colleagues. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R902]

Stress management differs widely based on how an individual perceives and relates stress to himself or herself, so a similar situation might trigger different responses. When I am stressed with work, I spend more time with my family and children. Self-care is the major approach all of us take. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R203)]

Capacity-building, Supervision and Support for Accompaniers

This section reviews the capacity, supervision, and support for accompaniers regarding stress management and coping in relation to programme operation and execution.

Most of the accompaniers interviewed said that they were satisfied with the training and supervision that they had been offered. However, many also felt that their capacity to work as accompaniers would have been greater if they had received more training in advanced-level counselling skills. They said that, if they had been given training, they would have been able to handle specific issues that arose while they were providing support instead of having to say, “Wait, I’ll consult my supervisor and then answer your question later.”

Most accompaniers were happy and stated that the training they received empowered them and proved to be effective in handling issues and dissipating the stresses, both personal and familial, which they encountered during the family sessions.

The accompaniers said that support from the ICRC was a major motivation. The accompaniers found relevant solutions to both personal and professional problems through consultation.

One counsellor said:

Whenever I find myself with a problem, the first thing I do is to share it with the local ICRC officer and other ICRC officials in Kathmandu. I have received significant help with both personal and professional problems. ICRC staff members really have a great deal of compassion for all of us working in the programme. — Female Counsellor, Chitwan (R206)

Although we do respect hierarchy, we feel that we belong to one family and that we are working for one cause. This sense of cooperative togetherness applies not just in our working districts but also with other accompaniers and staff all over the nation. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R202)

A five-day-long training on topics such as rapport-building, communication skills, responding skills, problem-solving, counselling skills, conducting household surveys and resource-mapping for referrals was provided to accompaniers immediately after their recruitment through adult learning methodologies, including role-plays for each set of skills. Other training included facilitation skills, support-group protocol, income-generating activities, and an orientation meeting with local stakeholders. The continued supervision and support made available to accompaniers were highly appreciated. Team cohesion was strong.

Proper support and coordination existed between team members. Help from colleagues and superiors was good. We always worked as a team. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Kathmandu (R506)

Socio-ecological Significance of Their Work

The socio-ecological model of wellbeing considers both individual and various other forces in active interplay and suggests that wellbeing is determined by a dynamic, complex and multidimensional process. Environmental factors, societal feedback, and individual personality all combine to determine the level of subjective wellbeing experienced by an individual (Sigelman & Rider, 2006).

When a member of a FoMPs starts working, he or she experiences a considerable boost to his or her self-confidence, and finds a platform to work, access to a network, and social recognition for a family that has been looked down upon. —Male non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R302)

The above statement is the perspective of a non-FoMPs accompanier on the benefits of the job for a FoMPs accompanier. He further suggested that the programme is significant in increasing the psychosocial well-being of FoMPs’ accompaniers.

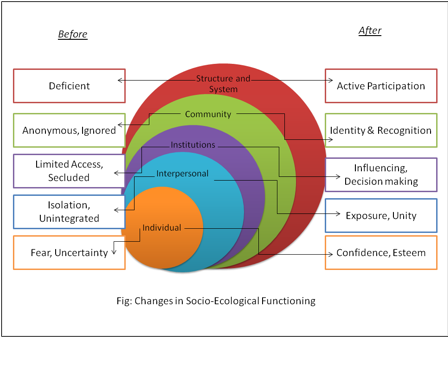

Figure 2

Figure 2 above compares the socio-ecological functioning of FoMPs’ accompaniers before and after they took up their positions in Hateymalo. It is based on an analysis of the information provided during interviews and FGDs. In terms of individual benefits, the accompaniers felt that their involvement in the programme helped them to develop confidence and self-esteem. Before their participation, they often felt they were living in continuous fear and insecurity. At the interpersonal level, they were isolating themselves and felt unintegrated; the program allowed them exposure, allowing them to see more people with similar suffering, and thus creating a sense of unity. At the institutional level, they were uninformed of available services and the mechanisms to access those services. After the program, they felt they were more knowledgeable; they engaged with governmental and non-governmental institutions and started influencing decision-making processes on behalf of the families of missing persons. At the community level, they were ignored, isolated, and not “known”; after working for the program, they were known in the community, and they gained recognition and respect. Overall, at the structural and systemic level, while they were deficient before the program, they grew to be active participants, knowledgeable, and engaging at the structural level.

I wanted to be a part of this programme to learn new things. I experienced the pain of losing someone from my family and felt the programme would help me not only reduce my stress but also be of some significant help and support to people with similar woes and cries. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R101)

The program has been a major learning platform. It also gave me social recognition and an identity, both of which have been important contributors to my growth and development —Male FoMPs accompanier, Chitwan (R205)

I am glad that I was involved in a programme which helped FoMPs unite to find solutions to a common problem. It helped family members change themselves and embrace the positivity they needed to think, act and work for their common good. I am also thankful to the programme for helping me reduce both my own stress and that of FoMPs. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R201)

I learned to look forward to the future and to forget my pains. This has been significant for my personal and professional growth. —Male-FoMPs, Kathmandu (R306)

The programme also helped to eliminate various ill practices prevalent in society, and the way FoMs are perceived by other members of society has changed drastically. When I see these changes, I have no regrets about being a part of this programme to bring about social change. —Female-FoM, Nepalgunj (R201)

The other important aspect of this programme was that it mitigated the hatred that was omnipresent between the state and rebel FoMs. Initially, the two types of FoMPs would not even speak to each other, but, through our efforts, they realised that solving their common problems was more significant than their political affinities and started helping each other. —Female FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R101)

The programme was helpful for personal growth and development through my participation in efforts to reduce my own stress as well as that of families and groups. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R102)

I feel the programme provided us an avenue to learn new things. By working on what we were taught, I am sure we all have developed attributes of personal and professional growth. I found a job after the programme was phased out of my district. —Female non-FoMPs accompanier, Nepalgunj (R402)

In summary, the wounded healer archetype offers a profound understanding of the human dimension within the helping professions. It acknowledges that personal suffering, rather than being a deficit, can be transmuted into a powerful resource for connection, empathy, and healing when approached with consciousness and integrity. Rooted in Jungian thought and ancient myth, the concept highlights the potential for therapists to leverage their lived experiences to foster deeper therapeutic alliances and model resilience. However, the archetype also carries inherent risks, primarily related to unintegrated wounds manifesting as countertransference, boundary violations, or burnout. Therefore, the ethical and effective embodiment of the wounded healer necessitates a steadfast commitment to ongoing self-awareness, personal therapy, supervision, and the conscious integration of one's own vulnerabilities. Ultimately, the wounded healer reminds us that strength and vulnerability are often intertwined, and that embracing our shared humanity is central to the art of healing.

Conclusions, Limitations and Further Research

The study findings showed that over two-thirds of individuals who served as accompaniers from FoMPs or Non-FoMPs did not suffer from severe stress or re-traumatization. Accompaniers, involved in this study, found hope, dignity, identity, opportunities, and pride due to their service. The engagement of FoMPs accompaniers has been of significant benefit not only to the accompaniers and families but also for the programme as a whole. There is no question that stress exists in the programme, but employing FoMPs members as accompaniers can be an effective strategy. They facilitate the sharing of issues and create social support much easier than their counterparts. Operating the programme with FoMPs has increased their sense of ownership and the degree of trust between FoMPs and accompaniers. The FoMPs accompaniers saw significant improvements in their social status, personal development, and ability to connect with FoMPs. All accompaniers have devised ways of coping with stress and cultivating a positive outlook toward the offerings of life. Further efforts to build their capacity would give them a considerable morale boost and increase their overall personal and professional well-being. Having access to a support system through referral and networking has helped accompaniers not only to connect FoMPs to the resources, but also use those services themselves. Accompaniers have capitalised on their learning experiences and exposures to increase their overall well-being.

These positive effects demonstrated that it is useful to recruit FoMPs’ accompaniers: they grow in self-confidence and can build good rapport with the target communities. The negative consequences for both groups were increased work-related stress and difficulty in working with families during the initial stages of their work as an accompanier. Exposure to the personal stories were stressful for one third of both cohorts of accompaniers. For one cohort, their personal memories were triggered, while for the other, secondary trauma was the factor.

The number of support and capacity-building initiatives for accompaniers was adequate. There is a need for periodic refreshers and updates of methods and modes of training. Accompaniers have been able to reduce their personal levels of stress through the opportunity for participation, economic support, self-empowerment, and learning that the programme offers. They have acquired the ability to manage the past, connect to the present, help others, and promote development to secure the future.

This research has many limitations. The study only included ‘wounded healers’ working for the families of missing persons in relation to the armed conflict, and there was no other comparable data available to outline whether these findings also apply to other categories of affected populations, such as survivors of other forms of trauma. This research was conducted with the staff members working in the same program, so human biases in providing information towards favouring the program implementation or the implementing institution could be a factor of bias.

Researchers realised that the questionnaire applied was locally developed and tested immediately, without proper psychometric testing. It is recommended to test the psychometric properties and validate the tools in future research.

Despite such limitations and potential human bias, this study, as far as the researchers know, is the first one in the accompaniment program implemented by the ICRC that tried to tackle the issue of involvement of ‘FoMPs’ as healers. The study also compared the information from the accompaniers representing non-relatives of missing persons. The study findings can be considered primary information gathered in supporting the unresolved issue of potential harm or empowerment of the ‘wounded healers’ supporting people suffering from similar pain. Further research in comparing these findings with other contexts where similar practices are done could provide more insights into validating the concept of wounded hearts as agents of change.

Acknowledgement

The authors sincerely thank and acknowledge Mr Subhash Chandra Sharma, clinical psychologist, and Mr Pranab Dahal (Second Author), who provided technical support in this study. The authors express gratitude to the excellent contributions of the accompaniers and staff members in the Hateymalo program, as well as their participation in this study. The authors also provide sincere thanks to the ICRC’s management team in Nepal for their encouragement and approval to conduct this study.

Ethics

Every respondent provided prior consent. Verbal consent was sought and granted to record the FGDs and interviews. The Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC), with approval no. 166/2013 dated on 27 April 2014, provided ethical approval for the research.

Funding

This study was part of the accompaniment program of the ICRC and carried out as a component of program activity. No external funding was secured.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests for this research.

Data availability

The anonymised dataset of quantitative data generated and analysed during the current study is available on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16944379. The qualitative analysis data with coding and quotes can be found at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16944425

References

Adhikari, Y. (2018). Compassion fatigue into the Nepali counselors: challenges and recommendations. MOJ Public Health, 7(6), 376‒379. https://doi.org/10.15406/mojph.2018.07.00271

Adhikari, Y. (2020). A comparative study of the Professional Quality of Life Factors in Nepali MHPSS Practitioners. Advanced Research in Psychology, 1(1), 1-112. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16423124

Andersen, I., Poudyal, B., Abeypala, A., Uriarte, C., & Rossi, R. (2020). Mental health and psychosocial support for families of missing persons in Sri Lanka: A retrospective cohort study. Conflict and health, 14(1), 1-16) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00266-0

Ardito, R. B., & Rabellino, D. (2011). Therapeutic Alliance and Outcome of Psychotherapy: Historical Excursus, Measurements, and Prospects for Research. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(270). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270

Boss, P. (2002). Ambiguous loss in families of the missing. The Lancet, 360, s39-s40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11815-0

Cherepanov, E. (2018). Ethics for global mental health: from good intentions to humanitarian accountability. Routledge.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.127.1.87

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, Eudaimonia, and Well-being: an Introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1

Dimitriadis, C. (2025). Humanitarian helper wellbeing: A psychosocial refugee care approach (Doctoral dissertation, University of Essex). https://repository.essex.ac.uk/41183/1/PhD%20Thesis%20in%20Refugee%20Care%20PPS%20Dimitriadis%20%28revised%29.pdf

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Guthrie, I. K. (1997). Coping with stress: The roles of regulation and development. In Handbook of children’s coping: Linking theory and intervention (pp. 41-70). Boston, MA: Springer US.

Figley, C. R. (2013). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Routledge.

Guggenbühl-Craig, A. (1971). Power in the helping professions. Spring Publications.Horvath, A. O., & Symonds, B. D. (1991). Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0167.38.2.139

Hayes, J. A., Gelso, C. J., Goldberg, S., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2018). Countertransference management and effective psychotherapy: Meta-analytic findings. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 496-507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pst0000189

Hunter, E. O. (2021). Relationship between wellness, resilience, and vicarious trauma among clinical mental health counselors serving interpersonal violence survivors (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University). https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=11923&context=dissertations

ICRC (2016). Hateymalo accompaniment programme: ICRC's comprehensive psychosocial support programme to the families of missing persons in Nepal (2010-2016). Retrieved from https://www.icrc.org/en/download/file/26584/hateymalo_accompaniment_report.pdf

Izquierdo, R., Makhashvili, N., Drožđek, B., & Wenzel, T. (2018). Mental Health and Well-Being of the Staff Supporting Refugees: How to Deal with Risks?. In An uncertain safety: Integrative health care for the 21st century refugees (pp. 363-384). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

James, L. E., Noel, J. R., Favorite, T. K., & Jean, J. S. (2012). Challenges of post disaster intervention in cultural context: The implementation of a lay mental health worker project in post-earthquake Haiti. International Perspectives in Psychology, 1(2), 110-126. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028321

Jung, C. G. (1966). Fundamental questions of psychotherapy. In H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, & W. McGuire (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung, 16, 111–125. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1966). Problems of modern psychotherapy. In H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, & W. McGuire (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung, 16, 53–75. Princeton University Press.

Kolden, G. G., Klein, M. H., Wang, C.-C., & Austin, S. B. (2011). Congruence/genuineness. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022064

Kraybill, O. G. (2015). Experiential training to address secondary traumatic stress in aid personnel. Lesley University.

Lazarus, R. S. (1993). From Psychological Stress to the Emotions: A History of Changing Outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology, 44(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2010). Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting Mixed Research in the Field of Counseling and Beyond. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00151.x

Li, G., Shi, W., Gao, X., Shi, X., Feng, X., Liang, D., ... & Hall, B. J. (2024). Mental health and psychosocial interventions to limit the adverse psychological effects of disasters and emergencies in China: A scoping review. The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific, 45, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. lanwpc.2022.100580

McGlinchey, D., & Killian, K. D. (2025). Helping Others While Helping Yourself: Vicarious Resilience in Victim Service Workers With and Without Experiences of Victimization. Journal of Social Service Research, 51(2), 466-473. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2024.2429668

Miller, G., & Baldwin, D. C., Jr. (2000). Implications of the wounded-healer paradigm for the use of self in therapy. In M. A. Hubble, B. L. Duncan, & S. D. Miller (Eds.), The heart & soul of change: What works in therapy (pp. 409–426). American Psychological Association.

Park, N. (2004). The Role of Subjective Well-Being in Positive Youth Development. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260078

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., ... & Unützer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The lancet, 392(10157), 1553-1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

Poudyal, B.N., & Adhikari, Y. (2022). Mental health in low- and middle-income countries: Needs, gaps, practices, challenges, and recommendations. In Adhikari, Y., Shrestha, S., & Sigdel, K. (2022). Nepalese Psychology: Volume One (pp.195-229). Evincepub. India: Chattisgarh.

Rathod, S., Pinninti, N., Irfan, M., Gorczynski, P., Bruce, M., & Jacob, K. S. (2017). Mental health service provision in low- and middle-income countries. Healthcare, 5(3), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632917694350

Sedgwick, D. (1994). The wounded healer: Countertransference from a Jungian perspective. Routledge.

Sigelman, C. K., & Rider, E. A. (2022). Life span human development (10th ed.). Cengage Learning Australia.

Skinner, E. A., & Wellborn, J. G. (2019). Coping during childhood and adolescence: A motivational perspective. In Life-span development and behavior (pp. 91-134). Routledge.

Snyder, C. R. (Ed.). (1999). Coping: The psychology of what works. Clarendon Press.

Welton-Mitchell, C. E. (2013). UNHCR’s mental health and psychosocial support. Geneva: UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/fr-fr/sites/fr-fr/files/legacy-pdf/51f67bdc9.pdf

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., ... & Vos, T. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 382(9904), 1575-1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6

World Health Organization. (2008). Task-shifting: Rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: Global recommendations and guidelines. WHO Press. https://chwcentral.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Task-Shifting-Global-Recommendations-and-Guidelines_0.pdf

World Health Organization. (2022). Mental Health Atlas 2020. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036703

Zerubavel, N., & Wright, M. O. (2012). The dilemma of the wounded healer. Psychotherapy, 49(4), 482–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027824