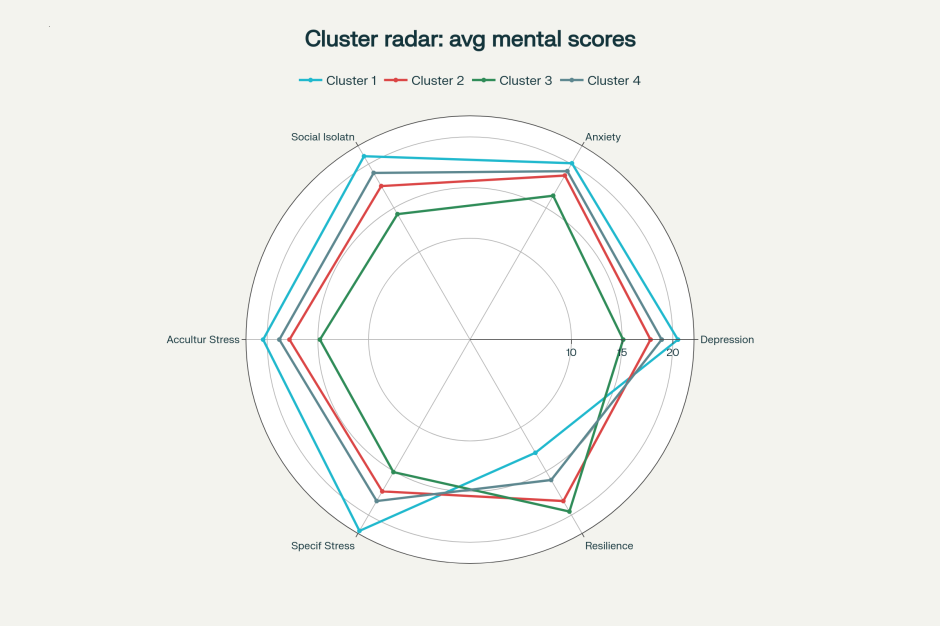

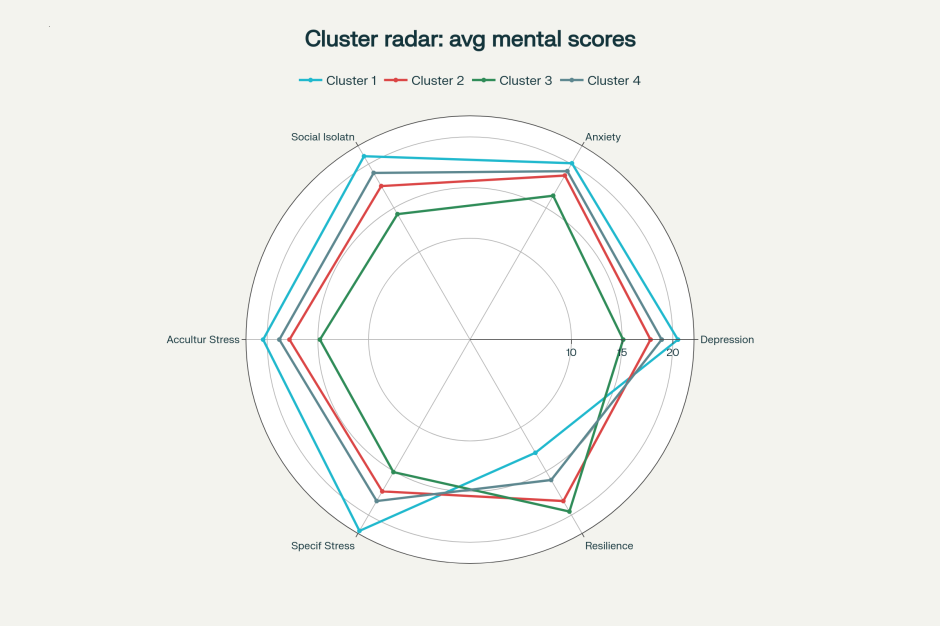

Figure 1 Radar of Average Psychological Scores by Cluster (n=4)

Mental Health and Social Isolation among Sub-Saharan African Migrants in Tunisia: A Cross-Sectional Quantitative Study {under peer review}

Research article

Zyed

Achour, Department of Labor Sciences, National Institute of Labor and Social

Studies, University of Carthage, Tunis, Tunisia, ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1578-9062

Background: Sub-Saharan African migrants in Tunisia are exposed to multiple psychosocial stressors that affect their mental health, yet few quantitative studies have examined these issues in this context.

Objective: To assess the prevalence and determinants of psychological distress among Sub-Saharan African migrants living in Greater Tunis, by analysing the role of social isolation, acculturative stress and psychosocial resources, and by identifying homogeneous clinical profiles through a clustering approach.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 98 migrants recruited in working-class neighbourhoods of Greater Tunis between March and June 2025, using convenience sampling combined with a time–location approach. Standardised composite scales were used to measure depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, social isolation, acculturative stress, specific stressors, and psychosocial resources. Analyses included descriptive statistics, bivariate comparisons, Pearson’s correlations, one-way ANOVA, and K-means clustering.

Results: Participants (mean age 26.7 ± 6.9 years; 53.1% men) recorded high mean scores for depression, anxiety and social isolation. Social isolation was moderately and significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.47, p < 0.001). Men reported higher depression scores than women. No significant differences were found by length of stay or legal status. Clustering analysis identified four distinct clinical profiles, ranging from severe distress with low psychosocial resources to low symptom levels with high resilience. These profiles also reflected variations in age, migration trajectories, and the perception of Tunisia as a transit country to Europe, a view frequently expressed by participants in informal discussions during fieldwork.

Conclusions: Psychological distress is widespread among Sub-Saharan African migrants in Tunisia and is shaped by social isolation, gender‑specific vulnerabilities, and persistent structural barriers. The identification of distinct clinical profiles highlights the heterogeneity of needs and underlines the importance of tailored mental health interventions that are culturally sensitive and responsive to gender differences.

Keywords: migration, mental health, social isolation, acculturative stress, resilience, North Africa, clustering analysis

Introduction

Since the Tunisian revolution of 2011, Tunisia has experienced considerable changes in its migratory landscape. Alongside traditional emigration flows, the country has emerged as a transit and host nation for numerous migrants, particularly those from sub-Saharan Africa. The post-revolutionary years witnessed a marked rise in migration flows towards and through Tunisia, occurring within a broader context of sustained economic and political instability. This situation became further complicated following the COVID-19 pandemic, which altered migratory routes whilst increasing the vulnerability of migrants residing in Tunisia.

Recent figures demonstrate the scale of these movements. During 2024, Tunisian authorities intercepted over 80,000 irregular migrants, predominantly from sub-Saharan regions, whilst approximately 18,300 refugees and asylum seekers were registered within the country (UNHCR, 2024). These statistics highlight unprecedented levels of migration flows, with Tunisia now functioning as a principal transit route towards Europe.

Such figures, based primarily on official interceptions and registered refugees, provide only a partial picture of the total sub-Saharan migrant population present in Tunisia. Many operate within informal networks under precarious circumstances. Recent research confirms that Tunisia is predominantly viewed by these migrants as a transit country towards Europe rather than a destination for permanent settlement (Global Initiative, 2024; Small Arms Survey, 2024).

The COVID-19 pandemic has particularly worsened existing hardships faced by these migrants, affecting their access to employment and healthcare whilst exacerbating their social precarity. This post-COVID context, when combined with structural challenges inherited from the post-revolutionary period, intensifies psychosocial and psychiatric risks for these migrant populations. Understanding the particular nature of this vulnerability within the Tunisian context is therefore essential for adapting mental health interventions and public policies to effectively address the needs of these migrants in complex circumstances.

Theoretical Framework

The biopsychosocial model developed by Engel (1977) provides a robust framework for understanding the mental health of migrants. It emphasises the interplay between several dimensions: biological factors, psychological aspects—such as coping strategies and how individuals interpret their situation—as well as social influences. It is precisely this complexity of interactions that makes this model relevant to migrant populations, where individual experiences intertwine with often challenging social and cultural contexts. Thus, mental health among migrants results from a delicate balance between individual predispositions, psychological stress, and social conditions (Engel, 1977; Roberts, 2023).

Social Isolation and Mental Health

Social isolation is a recognised cause of mental health problems among migrants worldwide. The breakdown of social networks, language barriers, cultural differences, and discrimination can all lead to profound feelings of loneliness and disconnection. This isolation manifests in two ways: objectively, through a real lack of contact or support, and subjectively, through the perception of being excluded or isolated (Nguyen et al., 2024; Ben Abid et al., 2023).

Several studies have shown that social isolation is linked to symptoms of depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress. Among migrants and refugees, this isolation often interacts with socioeconomic status to increase the risk of mental disorders (Nguyen et al., 2024; Ben Abid et al., 2023; Hajak et al., 2021). Although the majority of research focuses on Western contexts, there is a growing awareness that these links also apply in different sociocultural contexts, such as North Africa (Torabian, 2019).

Acculturative Stress

Acculturative stress refers to the psychological strain associated with adapting to a new culture. It is often associated with increased depression and anxiety among migrants. Berry (1997) proposes a key model that identifies four pathways of acculturation: integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalisation, each with a different impact on psychological well-being. Acculturative stress can manifest itself in various challenges: language difficulties, value conflicts, feelings of exclusion, and loss of identity (Berry, 1997; Nguyen et al., 2024).

Research shows that this stress significantly predicts mental health disorders among migrants, including depression and anxiety (Nguyen et al., 2024; Hajak et al., 2021). The process of social adaptation and coping with experiences of exclusion or discrimination constantly demands migrants' psychological resources (Nguyen et al., 2024).

Gender Differences

Gender plays an important role in migration experiences and mental health outcomes. Generally, migrant women show higher rates of mental health disorders, linked to specific factors such as gender-based discrimination, limited economic opportunities, and forms of social isolation (Hollander et al., 2011; Martin, 2023). However, more recent studies highlight the complexity of this relationship, with some observing increased suffering among men in specific contexts (Silove et al., 2017; Ben Abid et al., 2023).

Gender inequalities in mental health reflect multiple social determinants, such as access to resources, social roles, and exposure to trauma (Martin, 2023; Hajak et al., 2021). Understanding these nuances is essential for developing tailored and gender-sensitive interventions. 1.5 Study

Objectives

This study aims to:

1. Assess the prevalence and intensity of mental health symptoms (depression, anxiety, social isolation, acculturative stress) among sub-Saharan migrants in Tunisia;

2. Explore the direct and intersecting relationships between social isolation, acculturative stress, psychosocial resources, and mental health conditions;

3. Identify the main demographic, migratory, and contextual factors associated with psychological distress, considering the country's role as a transit area;

4. Analyse mental health differences by gender and age, and the sources of vulnerability specific to each subgroup;

5. Highlight, through clustering analysis, homogeneous clinical profiles to better understand the diversity of situations and adapt interventions in the field.

Methods

Study design and setting

This quantitative, cross-sectional study was conducted between March and June 2025 in Greater Tunis. We selected Greater Tunis as our research site for compelling practical reasons: it serves as both a hub and transit point for numerous sub-Saharan migrants, whilst encompassing bustling working-class neighbourhoods, active community organisations, and informal social spaces.

Our fieldwork concentrated primarily in working-class areas where migrants' daily lives unfold: local cafés, crowded souks, busy pavements near transport hubs, places of worship, and small restaurants popular with diaspora communities. We made a deliberate choice to approach participants within their own environments. This facilitated initial contact, though it also meant adapting to frequent interruptions and occasional wariness.

The manuscript complies with the STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies.

Participants and sampling

During fieldwork, we approached just over 300 individuals. Our inclusion criteria were straightforward: sub-Saharan migrants aged 18 or above, resident in Tunisia for at least three months, able to provide informed consent, and capable of responding in French, Tunisian Arabic, or English. We excluded the few individuals who spoke none of these languages.

We employed a combination of convenience sampling and time-location sampling to ensure diversity across demographics (gender, age, legal status, length of residence). Recruitment sites ranged from cafés and local markets to community centres and places of worship, including informal gathering points identified by community leaders.

Several migrants, particularly those without legal status, displayed considerable caution, fearing their responses might have repercussions. Some chose to withdraw mid-interview, whether from apprehension or time constraints. Ultimately, 98 complete questionnaires were retained for analysis. This sample size provides adequate statistical power for our primary analyses: >99% power to detect the observed correlation between social isolation and depression (r = 0.47), and >95% for gender-based group comparisons (d = 0.46). Exploratory analyses (ANOVA, clustering) benefit from sufficient sample size whilst acknowledging power limitations for detecting small effects.

Data collection procedure

Data were gathered through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire offered in French, Tunisian Arabic, or English according to participant preference. We personally conducted the majority of interviews, occasionally assisted by community mediators to help translate cultural nuances or allay particular concerns.

Before each interview, we took time to explain the study’s objectives, participants’ rights, and anonymity guarantees. Breaking the ice often proved necessary: informal discussion about participants’ countries of origin or reasons for coming helped establish a basic level of trust. Verbal consent was systematically obtained.

Measures

The questionnaire included sociodemographic and migration data (age, gender, country of origin, length of stay, legal status, education level, employment, previous mental health service use) and several psychological scales.

We used standardised composite scales for the main psychological variables. Depression was measured with six items including "I feel sad or downcast without apparent reason" and "I have lost interest in activities I used to enjoy." The anxiety scale had six items like "I worry excessively about my situation in Tunisia" and "I have difficulty falling asleep because of my worries."

Social isolation included items such as "I feel alone even when surrounded by other people" and "It is difficult for me to create bonds with Tunisians." For acculturative stress, we included "I feel lost between my origin culture and Tunisian culture" and "The language barrier causes me daily stress."

We also measured specific migration stressors with items like "My legal status in Tunisia constantly worries me" and "My housing conditions affect my mental wellbeing." The resources scale included "I find ways to cope with my difficulties" and "My faith/spirituality helps me overcome trials."

All items used 5-point Likert scales (1=never, 5=always). Composite scores ranged from 6 to 30. Higher scores meant more symptoms for depression, anxiety, isolation and stress scales, but more resources for the resilience scale.

We tested the questionnaire with five migrants before the main study. Two items were reworded based on their feedback about clarity.

In addition to these structured items, the questionnaire also included an open-ended section allowing participants to freely express their concerns and share their opinions in their own words.

Statistical analysis

Data entry and analysis were carried out using SPSS. We ran descriptive analyses to examine frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations for the main variables. We checked whether our data followed normal distributions using Shapiro-Wilk tests and by looking at histograms and Q-Q plots.

Most of our composite scores were normally distributed. Social isolation scores showed a slight departure from normality (p = 0.03), and specific stress scores were borderline (p = 0.05), but these deviations were minor enough that we could still use parametric tests without concerns about validity.

We used Pearson correlations to examine relationships between continuous variables. Gender comparisons relied on independent samples t-tests with Cohen's d for effect sizes. To look at differences by length of residence, we ran one-way ANOVA with three groups: less than 12 months, 12-36 months, and over 36 months. We set statistical significance at p < 0.05 and interpreted effect sizes using Cohen's conventions (small = 0.2, medium = 0.5, large = 0.8). We checked test assumptions before running any analyses.

We also did K-means clustering to find groups of participants with similar clinical and psychosocial profiles. Cross-correlations between different dimensions helped us understand direct and indirect relationships. We tested whether resilience moderated certain relationships and whether acculturative stress mediated the link between social isolation and depression. These additional analyses helped clarify the complex connections in our data.

Results

Sociodemographic and migration characteristics

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of our 98 participants. The sample was predominantly young men (mean age 26.7 years), with irregular status being the most common situation (58.2%). The most frequent countries of origin were Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea and Mali. This pattern reflects both the diversity of sub-Saharan migration to Tunisia and the administrative precarity that characterises many migrants' experiences.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and migration characteristics (N = 98)

|

Variable |

Category |

n |

% |

|

Age (years) |

Mean ± SD |

26.7 ± 6.9 |

– |

|

Gender |

Male |

52 |

53.1 |

|

Female |

46 |

46.9 |

|

|

Legal status |

Regular |

27 |

27.6 |

|

Irregular |

57 |

58.2 |

|

|

In process |

14 |

14.3 |

|

|

Country of origin |

Côte d'Ivoire |

23 |

23.5 |

|

Guinea |

18 |

18.4 |

|

|

Mali |

15 |

15.3 |

|

|

Cameroon |

14 |

14.3 |

|

|

Senegal |

12 |

12.2 |

|

|

DR Congo |

11 |

11.2 |

|

|

Others |

5 |

5.1 |

|

|

Length of stay |

Mean ± SD (months) |

23.8 ± 13.5 |

– |

Psychometric reliability of instruments

We checked internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha coefficients. All scales showed good reliability, which confirmed our measurement approach worked well (Table 2 has the details).

Table 2 Internal consistency of the scales (Cronbach’s alpha, N = 98)

|

Scale |

Number of items |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Interpretation |

|

Depressive symptoms |

6 |

0.83 |

Good |

|

Anxiety symptoms |

6 |

0.79 |

Acceptable |

|

Social isolation |

6 |

0.85 |

Good |

|

Acculturative stress |

6 |

0.77 |

Acceptable |

|

Specific stressors |

6 |

0.75 |

Acceptable |

|

Social resources |

6 |

0.81 |

Good |

Psychosocial scores overview

Table 3 shows the main descriptive results. Participants reported high levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms alongside considerable social isolation. They also demonstrated substantial psychosocial resources. These scores indicate widespread mental distress across the sample.

Table 3 Descriptive scores for psychosocial dimension

|

Dimension |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

SD |

Median |

Q1–Q3 |

|

Depression |

11 |

26 |

17.6 |

3.8 |

18 |

15–20 |

|

Anxiety |

12 |

28 |

18.4 |

4.0 |

18 |

16–21 |

|

Social isolation |

10 |

26 |

17.9 |

3.9 |

18 |

15–21 |

|

Acculturative stress |

10 |

24 |

17.5 |

3.2 |

17 |

15–20 |

|

Social resources |

8 |

24 |

17.2 |

3.5 |

17 |

15–20 |

Social isolation and depression link

We found a moderate, highly significant correlation between social isolation and depressive symptoms. Additional analyses looking at moderating and mediating effects showed no significant influence of resilience or acculturative stress on this relationship (see Table 4).

Table 4 Pearson’s correlation between social isolation and depressive symptoms (N = 98)

|

Variable |

Social isolation |

Depression |

|

Social isolation |

1 |

0.47** |

|

Depressive symptoms |

0.47** |

1 |

Note: p < 0.001

Additional analyses using moderation (social resources as moderator) and mediation (acculturative stress as mediator) did not yield statistically significant interaction or indirect effects, indicating a direct and robust link between isolation and depressive symptoms.

Gender differences

Men had significantly higher depression scores than women. Other dimensions showed no notable gender differences (Table 5).

Table 5 Mean scores by gender

|

Dimension |

Men (n = 52) |

Women (n = 46) |

p-value |

Cohen’s d |

|

Depression |

18.4 (3.9) |

16.8 (3.6) |

0.018 |

0.46 |

|

Anxiety |

18.4 (4.2) |

18.3 (3.8) |

0.91 |

0.02 |

|

Social isolation |

18.1 (3.8) |

17.7 (4.0) |

0.65 |

0.10 |

|

Acculturative stress |

17.8 (3.4) |

17.2 (3.1) |

0.42 |

0.18 |

|

Social resources |

17.1 (3.7) |

17.2 (3.4) |

0.93 |

0.02 |

Length of residence effects

Grouping participants by time in Tunisia revealed no significant differences in mental health scores. Psychological distress and resources remained stable regardless of how long people had been in the country (full results in Table 6).

Table 6 Mean scores by length of stay

|

Dimension |

< 12 m (n = 18) |

12–36 m (n = 52) |

> 36 m (n = 28) |

F |

p-value |

|

Depression |

17.3 (3.9) |

17.9 (3.7) |

17.6 (3.8) |

0.20 |

0.82 |

|

Anxiety |

18.1 (3.9) |

18.7 (4.0) |

18.2 (3.9) |

0.23 |

0.79 |

|

Social isolation |

17.8 (4.0) |

18.0 (4.0) |

17.9 (3.8) |

0.02 |

0.98 |

|

Acculturative stress |

17.4 (3.3) |

17.6 (3.4) |

17.5 (3.0) |

0.02 |

0.98 |

|

Social resources |

17.0 (3.6) |

17.2 (3.4) |

17.5 (3.6) |

0.15 |

0.86 |

Legal status and symptom levels

Legal status (regular, irregular, in process) was not associated with significant variations in depression, anxiety, isolation or psychosocial resources. We observed only non-significant trends (Table 7).

Table 7 Mean scores by legal status

|

Dimension |

Regular (n = 27) |

Irregular (n = 57) |

Pending (n = 14) |

F |

p-value |

|

Depression |

17.1 (3.6) |

17.8 (3.8) |

17.6 (3.8) |

0.25 |

0.78 |

|

Anxiety |

18.2 (3.8) |

18.4 (4.0) |

18.5 (3.8) |

0.04 |

0.96 |

|

Social isolation |

17.4 (3.7) |

18.0 (3.9) |

17.8 (4.0) |

0.17 |

0.84 |

|

Acculturative stress |

17.2 (3.4) |

17.6 (3.3) |

17.5 (3.2) |

0.06 |

0.94 |

|

Social resources |

17.1 (3.5) |

17.3 (3.5) |

17.4 (3.6) |

0.03 |

0.97 |

Clinical profiles through clustering

Cluster analysis identified four distinct clinical profiles with specific combinations of symptoms and psychosocial resources (Table 8). This segmentation reflects the diversity of psychological experiences in our sample. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of these profiles.

Table 8 Clinical profiles identified through cluster analysis (N = 98)

|

Cluster |

n |

Depression |

Anxiety |

Isolation |

Accult. Stress |

Specific Stress |

Resilience |

Clinical profile |

|

1 |

24 |

20.5 (2.1) |

20.1 (2.3) |

20.9 (1.8) |

20.4 (1.9) |

21.8 (2.0) |

12.9 (2.4) |

Severe distress, low resilience |

|

2 |

26 |

17.8 (2.0) |

18.7 (2.1) |

17.5 (2.2) |

17.8 (1.8) |

17.3 (2.3) |

18.4 (1.7) |

Moderate distress, good resources |

|

3 |

27 |

15.1 (2.4) |

16.4 (2.0) |

14.3 (2.1) |

14.8 (2.2) |

15.1 (2.0) |

19.6 (1.9) |

Low symptoms, high resilience |

|

4 |

21 |

18.9 (2.2) |

19.2 (2.0) |

19.0 (2.3) |

18.8 (2.1) |

18.4 (2.4) |

16.0 (2.2) |

High distress, modest resources |

Note: Values are presented as means (standard deviation). Possible scores: 6-30 for each dimension. ANOVA analyses confirmed significant differences between clusters across all dimensions (p < 0.001).

The first group includes participants experiencing severe distress with high scores across all symptom dimensions and low resilience. The second group shows moderate distress but better preserved psychosocial resources. The third comprises a resilient profile with low symptoms and strong resources, while the final group presents high distress combined with moderate resilience.

This clustering highlights how complex migrants' lived experiences are and why interventions need tailoring to specific profiles. It also provides useful guidance for personalising clinical and community approaches.

Cluster analysis revealed four distinct clinical profiles within our sample (see Figure 1). These groups show considerable diversity in how psychological symptoms and psychosocial resources coexist among migrants. The differences are particularly evident in depression, anxiety, social isolation and resilience levels.

Figure 1 Radar of Average Psychological Scores by Cluster (n=4)

From a psychological perspective, the relatively young average age appears to influence these profile patterns. Younger participants, often engaged in recent and unstable migration journeys, mostly comprise groups showing higher resilience despite variable symptoms. This fits with the greater adaptability and plasticity typical at these ages, plus a form of optimism linked to early migration phases. Conversely, profiles with high distress and low resilience often include older individuals, potentially exposed to accumulated chronic stress from precarity and difficulties establishing themselves permanently in a transit country.

The transit dimension seems particularly central when interpreting results. Several qualitative interviews conducted alongside questionnaires revealed that many migrants don't view Tunisia as a permanent settlement but rather as a passage towards other European or alternative destinations. This constant transitional state promotes feelings of insecurity, uncertainty and isolation, which worsen psychological suffering and undermine attempts at social or cultural integration. These findings align with research highlighting the specific harmful mental health impacts of transit migration contexts (Caterina Gargano et al., 2022; Devillanova et al, 2024).

Religion also emerges as a major psychosocial factor. Many interviewed migrants valued their faith as an essential resource for coping with difficulties. Turning to spiritual and community practices provides structure, moral support and belonging, which can moderate negative effects of social isolation and acculturative stress. This sacred dimension, deeply rooted in sub-Saharan cultures, finds particular resonance in the Tunisian context, where religion occupies a central place in social life. This connection between religion, resilience and mental health deserves specific attention when developing appropriate clinical and community interventions.

Discussion

This study offers new quantitative insights into mental health issues among Sub-Saharan African migrants in Tunisia. This is a field still quite underexplored in scientific literature. The high average scores across all dimensions show a notable prevalence of psychological distress in this group. These findings confirm risks well outlined by the biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977; Silove et al., 2017) and many studies linking migration, precarity, and mental health (Hajak et al., 2021; Martin, 2023).

Social isolation and mental health: a confirmed link

Unlike an earlier version, detailed data analysis now reveals a moderate positive correlation between social isolation and depressive symptoms (r = 0.47, p < 0.001). This aligns with research that points to isolation as a major factor in mental distress among migrants (Bridger & Evans, 2019; Lim et al., 2022; Hajak et al., 2021).

Social isolation here means both lack of contact (objective isolation) and feelings of loneliness or exclusion (subjective isolation). Such isolation harms integration and wellbeing (Torabian, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2024).

In Tunisia, though, some cultural and community factors seem to soften these effects. Transnational networks, the use of technology, and solidarity within the diaspora appear to provide resilience resources. These might be overlooked by standard Western measures.

This invites us to rethink how social isolation is measured and adapt tools to African realities, which are more collective and community-based than typical Western scales assume (Berkman & Glass, 2000).

Gender specificity: unexpected male vulnerability

One striking finding is the increased vulnerability of men to depressive symptoms. This runs counter to most epidemiological studies that find higher rates in women (Hollander et al., 2011).

This pattern, seen before in precarious migrant contexts (Martin, 2023; Silove et al., 2017), can be explained by several factors:

Men’s traditional roles (family provider, economic success) are tested by exile realities, precarity, and administrative hurdles. This causes identity conflicts and moral suffering (Hollander et al., 2011; Hajak et al., 2021).

Men are also less likely to show distress or seek support, which may worsen depressive symptoms (Touzel et al., 2025).

On the other hand, migrant women often hold stronger informal networks or are better able to seek help, offering psychological protection.

This highlights the need for clinical approaches sensitive to gender, particularly addressing male vulnerabilities in migration contexts (Silove et al., 2017).

Effects of length of stay: persistent vulnerability

Analysis by groups of length of stay (< 12 months, 12–36 months, > 36 months) showed no significant difference in mental health scores — whether depression, anxiety, social isolation, acculturative stress, or psychosocial resources. This suggests simply staying longer in Tunisia does not improve or worsen average psychological health.

An indirect time analysis used exact months of stay as a continuous variable. Results confirmed no significant variation in most indicators, except for a slight but significant linear decrease in specific stress over time (coef. = -0.0486; p = 0.046). This small drop could reflect gradual adaptation to practical issues (housing, navigating the city, informal healthcare access). Still, this minor positive change isn’t seen in general mental health measures.

We interpret this in Tunisia’s particular migration context. Many respondents said informally that they see the country mainly as a transit point to Europe rather than a permanent home. This “in-between” status fuels uncertainty and instability, blocking social rooting and long-term outlooks. The lack of legal status for most worsens this precariousness.

Clinically, stable scores over time show mental suffering is not just from an initial settlement shock. It persists due to chronic structural factors: little integration prospects, discrimination, limited resource access, short-term survival strategies.

In other words, time alone does not heal in this context. Without targeted interventions and better living conditions, mental health trajectories stay stuck or may deteriorate.

Clinical and policy implications

Our findings call for rethinking migrant mental health policies:

Services must be gender- and culture-sensitive, recognising male-specific experiences and cultural distress expressions (Hajak et al., 2021).

Interventions should consider complex support sources among African migrants: transnational ties, diaspora solidarity, religious or community practices (Nguyen et al., 2024).

It is essential to tackle structural causes of mental distress: legal precarity, stigma, barriers to work and mental healthcare (Côté-Olijnyk et al., 2024).

Community strategies that empower associations, migrant intermediaries, and collective support rituals are key to countering social isolation and its harms.

Limitations of the study

This study stands out for its use of standardised measurement tools combined with a rigorous statistical approach applied in a context that is both sensitive and difficult to access. The strategy for recruitment, covering a diversity of neighbourhoods and participant profiles, allowed for a richer overview of the realities faced by sub-Saharan African migrants living in Greater Tunis. By integrating multiple dimensions of mental health – depression, anxiety, social isolation, acculturative stress and psychosocial resources – the analysis captures the complexity of their psychosocial condition in a more nuanced and realistic way.

However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design does not allow any causal relationship to be established between the variables studied. Measures of social isolation, although valid, were developed in Western contexts and may not fully reflect the cultural specificities of African migrant communities, where collective and community ties often take forms not captured by conventional scales. The exclusive use of self-reported questionnaires may have introduced a social desirability bias, which could be stronger among participants with irregular migration status. Finally, as data collection took place solely in the Greater Tunis area, the results cannot be generalised to all migrant populations in Tunisia, particularly those in other regions facing different local challenges.

Research perspectives

Several avenues can be explored to deepen our understanding of migrant mental health in North Africa. Longitudinal approaches would make it possible to follow trajectories of adaptation over time and to compare situations of exile with more settled forms of migration. Mixed-method designs, combining quantitative measurement with qualitative exploration of lived experiences, informal support networks and the meaning attributed to migration, would provide a more complete picture. Particular attention should be paid to culturally adapting and validating tools that can measure forms of isolation, resilience and collective resources specific to African societies. There is also a need for intervention research testing culturally sensitive, community-based and gender-responsive clinical models. Finally, comparative studies in different national contexts could shed light on what is specific to Tunisia and what stems from broader regional or global dynamics of migration and mental health.

This study reveals a striking picture of mental health among sub-Saharan African migrants in Tunisia, marked by multidimensional psychological distress and consistently high average scores for depression, anxiety, social isolation and acculturative stress. Within these findings, one relationship is particularly revealing: the moderate, statistically significant association between social isolation and depressive symptoms, a link long suggested by international research and clearly confirmed here. Just as noteworthy is the reversal of an expected trend: male participants reported higher depression scores than their female counterparts, challenging prevailing epidemiological assumptions and pointing towards gendered pressures linked to migration, economic hardship and cultural expectations.

The persistence of distress regardless of length of stay or legal status reflects a deeper structural reality. Time spent in the host country brings little relief when daily life is framed by uncertainty, administrative limbo, discrimination and restricted access to work or healthcare. Vulnerability here is not a temporary state, but one sustained by systemic barriers that blunt opportunities for adaptation and recovery.

These patterns carry implications that reach beyond the clinical setting. Mental health care for migrants must be both culturally grounded and gender-sensitive, attuned to the specific ways distress is expressed and addressed in African contexts. It should be accessible to all, independent of legal status, and supported by trained interpreters and cultural mediators. Community-based networks—diaspora associations, faith groups, informal peer support—are not auxiliary; they are central to any credible strategy for reducing isolation and strengthening resilience. Structural action is equally urgent: clearer routes to legal regularisation, anti-discrimination measures in employment, and the integration of mental health into national and regional migration policy would signal the seriousness of these issues.

The psychological suffering documented here is both an individual burden and a public health concern. Addressing it will demand sustained collaboration between healthcare systems, policymakers and community organisations. Imported, generic care models will not suffice; interventions must be shaped by empirical evidence drawn from the local migration context. As migration flows through North Africa continue, there is an urgent need for ongoing research, innovative policy and cross‑sector partnerships. This study offers a foundation for that work, bringing empirical depth and methodological clarity to a subject too often left at the margins, and underscoring the responsibility to act.

Author Contributions

The author conceived and designed the study, carried out all stages of data collection in the field, performed the statistical analyses, and interpreted the results. The author also drafted and revised the manuscript in its entirety, taking full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work.

Use of AI Technology

The author used AI-based tools to support language refinement, verify the coherence of interpretations related to statistical models, generate summaries of selected academic references, and assist in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Ethics Statement

The study involved voluntary and anonymous participation of individuals responding to a mental health questionnaire. All participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in the study. Anonymity and confidentiality of personal information were strictly guaranteed, and participation was entirely voluntary. No financial or material compensation was provided. According to the applicable national and institutional guidelines, this study did not require formal approval from an Ethics Review Board. Therefore, no ethical approval number, issuing institution, or date is applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymised dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16898336

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The author warmly thanks all participants for their trust and openness, as well as the local organisations and migrant community leaders whose support helped make recruitment possible. Particular appreciation is extended to the cultural mediators and field assistants whose involvement ensured that data collection was conducted with respect, cultural sensitivity, and care.

References

Ben Abid, I., Ouali, U., Ben Abdelhafidh, L., & Peterson, C. E. (2023). Knowledge, attitudes and mental health of sub-Saharan African migrants living in Tunisia during COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychology, Advance online publication, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04607-z

Berkman, L. F., & Glass, T. (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In L. F. Berkman & I. Kawachi (Eds.), Social Epidemiology (pp. 137–173). Oxford University Press.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Bridger, O., & Evans, R. (2019). Tackling loneliness and social isolation in Reading (Research Report). Participation Lab, University of Reading. https://images.reading.gov.uk/2020/10/Bridger-and-Evans-2019-Tackling-Loneliness-in-Reading-report.pdf

Côté-Olijnyk, M., Perry, J. C., Paré, M. È., & Kronick, R. (2024). The mental health of migrants living in limbo: A mixed-methods systematic review with meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 337, 115931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2024.115931

Devillanova, C., Franco, C., & Spada, A. (2024). Downgraded dreams: Labor market outcomes and mental health in undocumented migration. SSM - Population Health, 26, 101652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2024.101652

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Gargano, M. C., Ajduković, D., & Vukčević Marković, M. (2022). Mental health in the transit context: Evidence from 10 countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063476

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. (2024). Tunisia: Irregular migration reaches unprecedented levels. GI-TOC. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Tunisia-Irregular-migration-reaches-inprecedented-levels-GI-TOC-August-2024.pdf

Hajak, V. L., Sardana, S., Verdeli, H., & Grimm, S. (2021). A systematic review of factors affecting mental health and well-being of asylum seekers and refugees in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 643704. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643704

Hollander, A.-C., et al. (2011). Gender-related mental health differences between refugees and non-refugee immigrants: A cross-sectional register-based study. BMC Public Health, 11, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-180

Lim, M., Van Hulst, A., Pisanu, S., & Merry, L. (2022). Social isolation, loneliness and health: A descriptive study of the experiences of migrant mothers with young children (0–5 years old) at La Maison Bleue. Frontiers in Global Women's Health, 3, 823632. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.823632

Martin, F. (2023). The mental health of adult irregular migrants to Europe: A systematic review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 25(2), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-022-01379-9

Nguyen, T. P., Al Asaad, M., Sena, M., & Slewa-Younan, S. (2024). Loneliness and social isolation amongst refugees resettled in high-income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 360, 117340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117340

Roberts, A. (2023). The biopsychosocial model: Its use and abuse. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 26(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-023-10150-2

Silove, D., Ventevogel, P., & Rees, S. (2017). The contemporary refugee crisis: An overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20438

Small Arms Survey. (2024). Security over people: Tunisia's immigration crisis – Situation update October 2024. Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies. https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/resource/security-over-people-tunisias-immigration-crisis

Torabian, D. (2019). Home and healing in the in-between: Migrant and refugee mental health in Tunisia (Independent Study Project No. 3055). SIT Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4082&context=isp_collection

Touzel, V., Reifegerste, D., Bozorgmehr, K., & Biddle, L. (2025). Impact of social isolation on mental health changes by socio-economic status: A moderated mediation analysis among non-migrant, migrant, and refugee subpopulations in Germany, 2016–2020. SSM - Population Health, 31, 101822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2025.101822

UNHCR. (2024). Tunisia: Operational update June–August 2024. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. https://reliefweb.int/report/tunisia/unhcr-tunisia-operational-update-june-august-2024

STROBE Statement—checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies

|

|

||||

|

1 |

(a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract |

1 |

||

|

(b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found |

1 |

|||

|

Background/rationale |

2 |

Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported |

2 |

|

|

3 |

State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses |

2 |

||

|

4 |

Present key elements of study design early in the paper |

1&3 |

||

|

5 |

Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection |

3 |

||

|

Participants |

6 |

(a) Cohort study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants. Describe methods of follow-up Case-control study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of case ascertainment and control selection. Give the rationale for the choice of cases and controls Cross-sectional study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants |

3 |

|

|

(b) Cohort study—For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed Case-control study—For matched studies, give matching criteria and the number of controls per case |

Not applicable |

|||

|

7 |

Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable |

4 |

||

|

Data sources/ measurement |

8* |

For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group |

4 |

|

|

9 |

Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias |

3 & 5 |

||

|

10 |

Explain how the study size was arrived at |

3 |

||

|

Quantitative variables |

11 |

Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why |

4&5 |

|

|

Statistical methods |

12 |

(a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding |

5 |

|

|

(b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions |

5 |

|||

|

(c) Explain how missing data were addressed |

3 |

|||

|

(d) Cohort study—If applicable, explain how loss to follow-up was addressed Case-control study—If applicable, explain how matching of cases and controls was addressed Cross-sectional study—If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy |

3 |

|||

|

(e) Describe any sensitivity analyses |

Not applicable |

|||

|

Results |

||||

|

13* |

(a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—eg numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analysed |

Nearly 300 individuals were approached, but only 98 completed the interview. |

||

|

(b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage |

Several individuals were unavailable without providing a specific reason. |

|||

|

no flow diagram was used in this study. |

||||

|

Descriptive data |

14* |

(a) Give characteristics of study participants (eg demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders |

Sociodemographic and migratory characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1, page 10 |

|

|

(b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest |

No missing data were observed for key variables |

|||

|

(c) Cohort study—Summarise follow-up time (eg, average and total amount) |

Not applicable |

|||

|

15* |

Cohort study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time |

Not applicable |

||

|

Case-control study—Report numbers in each exposure category, or summary measures of exposure |

Not applicable |

|||

|

Cross-sectional study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures |

Outcome data are presented as summary measures (mean scores, standard deviations, medians) for key psychological dimensions: (pages 11 to 15 ) |

|||

|

16 |

(a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (eg, 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included |

No adjusted models were used |

||

|

(b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized |

Continuous variables were retained as scores |

|||

|

(c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period |

Not applicable |

|||

|

17 |

Report other analyses done—eg analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses |

Additional analyses included subgroup comparisons by gender, length of stay, and legal status (ANOVA), a K-means cluster analysis identifying four clinical profiles, and mediation/moderation tests between psychological dimensions. See Tables 5 to 8 |

||

|

18 |

Summarise key results with reference to study objectives |

A significant correlation was found between social isolation and depressive symptoms |

||

|

19 |

Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias |

Study limitations include selection bias resulting from the recruitment approach, as well as the absence of formal clinical data to validate psychological diagnoses. |

||

|

20 |

Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence |

The levels of psychological distress align with existing literature on vulnerable migrant populations. Observed correlations are interpreted as indicators of psychosocial vulnerability, without inferring causal relationships. |

||

|

21 |

Discuss the generalisability (external validity) of the study results |

The generalisability of findings is limited by the specific context of the study (Tunisia, vulnerable migrants) |

||

|

22 |

Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based |

This study received no external funding |

||