Mental Health and Social Isolation among Sub-Saharan African Migrants in Tunisia: A Cross-Sectional Quantitative Study {under peer review}

Research article

Zyed Achour, Department of Labor Sciences, National Institute of Labor and Social Studies, University of Carthage, Tunis, Tunisia, ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1578-9062

Background: Sub-Saharan African migrants in Tunisia face multiple psychosocial stressors affecting their mental health, yet quantitative evidence on psychological distress in this population remains scarce.

Objective: This exploratory study aimed to: (1) document self-reported symptom levels across multiple psychological dimensions, (2) examine the association between social isolation and depression, (3) identify variations by sociodemographic and migration-related characteristics, and (4) describe distinct symptom-resource profiles through cluster analysis.

Methods: Between March and June 2025, 98 Sub-Saharan migrants were recruited through time-location and convenience sampling in Greater Tunis. Structured interviews assessed depression, anxiety, social isolation, acculturative stress, and psychosocial resources using 6-item composite scales. Analyses included descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, t-tests, ANOVA, and k-means clustering.

Results: Mean symptom scores fell above theoretical scale midpoints: depression (M=17.6/30, SD=3.8), anxiety (M=18.4/30, SD=4.0), and social isolation (M=17.9/30, SD=3.9). Social isolation correlated moderately with depression (r=0.47, p<.001). Men reported higher depression than women (M=18.4 vs 16.8, p=.018, d=0.46). No differences emerged by length of residence or legal status. Cluster analysis identified four profiles: severe distress with low resilience (n=24), moderate distress with adequate resources (n=26), low symptoms with high resilience (n=27), and high distress with modest resources (n=21).

Conclusions: Sub-Saharan migrants in Tunisia report psychological symptom levels above scale midpoints, with social isolation strongly associated with depression and men showing unexpected vulnerability. The persistence of distress regardless of residence duration suggests structural rather than adjustment-related origins. Four distinct symptom-resource profiles highlight heterogeneity requiring differentiated intervention approaches. Findings underscore the need for gender-sensitive, community-based mental health support and policies addressing legal precarity.

Keywords: migration, mental health, social isolation, acculturative stress, resilience, North Africa, clustering analysis

Introduction

Since the 2011 Tunisian Revolution, Tunisia’s migration landscape has shifted in significant ways. In addition to its longstanding patterns of emigration, the country has increasingly become both a transit point and a temporary place of settlement for many migrants, particularly those from Sub-Saharan Africa. The post-revolution years have seen a marked rise in migration flows to and across Tunisia, unfolding within a broader context of persistent economic and political instability. These developments have gradually reshaped Tunisia’s role in regional mobility, leading to more complex and diverse migration trajectories. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic added an additional layer of difficulty by altering migration routes and further increasing the vulnerability of migrants living in the country.

Recent figures highlight the scale of this movement. In 2024, Tunisian authorities intercepted more than 80,000 migrants in an irregular situation—mostly from Sub-Saharan Africa—and around 18,300 refugees and asylum seekers were registered nationwide (UNHCR, 2024). While indicative of growing migration pressures, these numbers reflect only part of the reality. They mainly capture official interceptions and registered cases, leaving out many migrants who live in informal networks and under precarious conditions. Several recent studies show that most Sub-Saharan migrants view Tunisia not as a long-term destination but as a stopover on their way to Europe (Global Initiative, 2024; Small Arms Survey, 2024).

The COVID-19 pandemic further intensified the difficulties these migrants already faced, limiting access to employment and healthcare and exacerbating social and economic precarity. Combined with structural vulnerabilities that long predate the pandemic, this environment increases psychosocial risks and contributes to fragile mental health conditions. In such a context, documenting the levels of psychological distress among migrants—and examining how these relate to factors such as social isolation, acculturative stress, and psychosocial resources—becomes essential. Understanding these relationships within the specific Tunisian context is crucial for designing more responsive mental health interventions and informing public policies aimed at addressing the needs of migrants living in uncertain and often unstable circumstances.

Theoretical Framework

The biopsychosocial model developed by Engel (1977) provides a robust framework for understanding the mental health of migrants. It emphasises the interplay between several dimensions: biological factors, psychological aspects—such as coping strategies and how individuals interpret their situation—as well as social influences. It is precisely this complexity of interactions that makes this model relevant to migrant populations, where individual experiences intertwine with often challenging social and cultural contexts. Thus, mental health among migrants results from a delicate balance between individual predispositions, psychological stress, and social conditions (Engel, 1977; Roberts, 2023).

In this study, the biopsychosocial model serves as a guiding framework for understanding how social, psychological, and contextual factors jointly shape mental health outcomes among Sub-Saharan migrants in Tunisia. Social isolation represents the social dimension, perceived stress and emotional responses reflect the psychological dimension, and migrants’ living conditions capture key contextual components. This framework directly informs our research questions by positioning mental health outcomes as the result of interacting social and psychological determinants rather than isolated factors.

These theoretical frameworks directly inform our research design. Berry's acculturation model guides our measurement of acculturative stress as a key psychological stressor, while Engel's biopsychosocial framework structures our simultaneous examination of social factors (isolation, community resources), psychological dimensions (symptom endorsement, coping capacity), and contextual elements (legal status, migration duration). This integrated approach allows us to capture the multidimensional nature of migrant mental health, though we acknowledge that our exploratory cross-sectional design limits causal inference about how these dimensions interact.

Social Isolation and Mental Health

Social isolation is widely recognised as a significant determinant of psychological distress, particularly among individuals experiencing migration, displacement or socioeconomic vulnerability. For many migrants, separation from family networks, limited community ties, and unstable living conditions contribute to a reduced sense of belonging and heightened emotional strain. Previous research has shown that restricted social support often exacerbates symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, especially in contexts where daily life is marked by uncertainty or exclusion.

Recent systematic reviews further underscore how loneliness and weakened social networks affect the mental health of displaced populations. Nguyen et al. (2024) highlight the high symptom level of loneliness among refugees resettled in high-income countries and document its strong association with depression, PTSD and general psychological distress. Similarly, Nowak et al. (2023) show that post-migration living conditions—such as limited community ties, precarious housing and ongoing social exclusion—consistently predict elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety. These reviews collectively demonstrate that social isolation is a robust cross-contextual risk factor, reinforcing the relevance of examining this phenomenon in the Tunisian transit environment. Recent umbrella reviews further confirm social isolation as a critical public health concern requiring evidence-based interventions (Hansen et al., 2024).

Building on this broader evidence, several empirical studies have also linked social isolation to emotional exhaustion and reduced well-being among migrants facing socioeconomic insecurity. For instance, earlier work has shown that feelings of exclusion and limited interpersonal support directly contribute to depressive symptoms, while the absence of stable social networks increases psychological vulnerability. These findings reinforce the notion that isolation is not merely a social condition but a key psychological stressor that shapes how migrants adapt, cope and experience daily life. In the Tunisian context, where many Sub-Saharan migrants navigate precarious legal and economic situations, understanding these dynamics becomes all the more essential.

Bronfenbrenner's (1979) socio-ecological framework further enriches this perspective by emphasising how multiple system levels—from individual characteristics to family networks, community structures, and broader societal contexts—interact to shape adaptation to forced migration (Fadhlia et al., 2025). While our study focuses primarily on individual-level assessment, we acknowledge that participants' experiences are embedded within these nested ecological systems, which future research should examine more systematically.

Acculturative Stress

Acculturative stress refers to the psychological strain associated with adapting to a new culture. It is often associated with increased depression and anxiety among migrants. Berry (1997) proposes a key model that identifies four pathways of acculturation: integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalisation, each with a different impact on psychological well-being. Acculturative stress can manifest itself in various challenges: language difficulties, value conflicts, feelings of exclusion, and loss of identity (Berry, 1997; Nguyen et al., 2024).

Empirical studies consistently show that acculturative stress—rooted in language barriers, discrimination, unstable legal status and disrupted social networks—contributes directly to elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety among resettled and migrant populations. For example, Lumley, Katsikitis and Statham (2018) documented that acculturative stress was a substantive predictor of depression and anxiety in a sample of resettled Bhutanese refugees, while a study of Iraqi refugee women in the United States found a linear association between higher acculturative-stress scores and increased odds of both depression and anxiety (Yun et al., 2021). These findings suggest that acculturative stress operates through clear psychosocial pathways (limited support, exclusion, uncertainty) that are likely relevant to Sub-Saharan migrants in Tunisia and therefore merit explicit consideration in our analyses.

Research shows that this stress significantly predicts mental health disorders among migrants, including depression and anxiety (Nguyen et al., 2024; Hajak et al., 2021). The process of social adaptation and coping with experiences of exclusion or discrimination constantly demands migrants' psychological resources (Nguyen et al., 2024).

Gender Differences

Gender plays an important role in migration experiences and mental health outcomes. Generally, migrant women show higher rates of mental health disorders, linked to specific factors such as gender-based discrimination, limited economic opportunities, and forms of social isolation (Hollander et al., 2011; Martin, 2023). However, more recent studies highlight the complexity of this relationship, with some observing increased suffering among men in specific contexts (Silove et al., 2017; Ben Abid et al., 2023).

Gender inequalities in mental health reflect multiple social determinants, such as access to resources, social roles, and exposure to trauma (Martin, 2023; Hajak et al., 2021). Understanding these nuances is essential for developing tailored and gender-sensitive interventions.

Objectives

Given the severely understudied nature of this population, we designed this study as an exploratory investigation rather than a hypothesis-testing exercise. This study aims to:

- Document the prevalence and distribution of self-reported psychological symptoms (depression, anxiety, social isolation, acculturative stress) among Sub-Saharan migrants in Greater Tunis, recognizing that without validated diagnostic thresholds, findings represent symptom endorsement patterns rather than clinical prevalence estimates;

- Examine the bivariate association between social isolation and depressive symptoms, given prior evidence linking these dimensions in displaced populations;

- Describe variations in psychological symptom levels across key sociodemographic and migration-related characteristics (gender, age, length of residence, legal status) to identify potentially vulnerable subgroups;

- Identify distinct symptom-resource profiles through cluster analysis to capture heterogeneity in how psychological distress and coping capacity are configured within this population, informing future tailored intervention approaches.

These objectives provide an initial empirical portrait and generate hypotheses for future confirmatory research, without attempting to establish causal relationships. The study offers a foundation for understanding the psychosocial realities facing Sub-Saharan migrants in Tunisia, a population whose mental health needs have remained largely invisible in the scientific literature.

Methods

Study design and setting

This quantitative, cross-sectional study was conducted between March and June 2025 in Greater Tunis. We selected Greater Tunis as our research site for compelling practical reasons: it serves as both a hub and transit point for numerous sub-Saharan migrants, whilst encompassing bustling working-class neighbourhoods, active community organisations, and informal social spaces.

Our fieldwork concentrated primarily in working-class areas where migrants' daily lives unfold: local cafés, crowded souks, busy pavements near transport hubs, places of worship, and small restaurants popular with diaspora communities. We made a deliberate choice to approach participants within their own environments. This facilitated initial contact, though it also meant adapting to frequent interruptions and occasional wariness.

The manuscript complies with the STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies.

Participants and sampling

During fieldwork, we approached just over 300 individuals. Our inclusion criteria were straightforward: sub-Saharan migrants aged 18 or above, resident in Tunisia for at least three months, able to provide informed consent, and capable of responding in French, Tunisian Arabic, or English. We excluded the few individuals who spoke none of these languages.

We employed a combination of convenience sampling and time-location sampling to ensure diversity across demographics (gender, age, legal status, length of residence). Recruitment sites ranged from cafés and local markets to community centres and places of worship, including informal gathering points identified by community leaders.

Several migrants, particularly those without legal status, displayed considerable caution, fearing their responses might have repercussions. Some chose to withdraw mid-interview, whether from apprehension or time constraints. Ultimately, 98 complete questionnaires were retained for analysis. This sample size is adequate for our main objectives: it offers very high power to detect the observed association between social isolation and depression, as well as the difference in depression scores between men and women. For more exploratory analyses such as ANOVA and clustering, the sample remains acceptable, although the study is less well powered to identify small effects.

Data collection procedure

Data were gathered through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire offered in French, Tunisian Arabic, or English according to participant preference. We personally conducted the majority of interviews, occasionally assisted by community mediators to help translate cultural nuances or allay particular concerns.

Before each interview, we took time to explain the study’s objectives, participants’ rights, and anonymity guarantees. Breaking the ice often proved necessary: informal discussion about participants’ countries of origin or reasons for coming helped establish a basic level of trust. Verbal consent was systematically obtained.

Face-to-face interviews were chosen over self-administered surveys due to: (a) variable literacy levels among participants, (b) lack of private space for questionnaire completion in precarious housing conditions, and (c) mistrust of written documentation, particularly among irregular migrants. The primary author conducted all interviews in French and Tunisian Arabic.

Measures

The questionnaire included sociodemographic and migration data (age, gender, country of origin, length of stay, legal status, education level, employment, previous mental health service use) and several psychological scales.

We used standardised composite scales for the main psychological variables. Depression was measured with six items including "I feel sad or downcast without apparent reason" and "I have lost interest in activities I used to enjoy." The anxiety scale had six items like "I worry excessively about my situation in Tunisia" and "I have difficulty falling asleep because of my worries."

Social isolation included items such as "I feel alone even when surrounded by other people" and "It is difficult for me to create bonds with Tunisians." For acculturative stress, we included "I feel lost between my origin culture and Tunisian culture" and "The language barrier causes me daily stress."

In this study, psychosocial resources refer to perceived emotional support, informal community assistance, and access to basic aid networks. These resources were measured as perceived availability rather than confirmed utilization, allowing us to assess respondents’ sense of having someone or something to rely on, even if not activated at the time of the survey.

The items captured respondents’ perceptions of support availability rather than the frequency of actual use, a distinction consistent with prior research showing that perceived support is itself a strong predictor of psychological outcomes.

We also measured specific migration stressors with items like "My legal status in Tunisia constantly worries me" and "My housing conditions affect my mental wellbeing." The resources scale included "I find ways to cope with my difficulties" and "My faith/spirituality helps me overcome trials."

Resilience was assessed through items reflecting respondents’ perceived ability to cope with stress, maintain emotional stability and adapt to adverse circumstances; higher scores reflected stronger perceived coping capacity.

All items used 5-point Likert scales (1=never, 5=always). Composite scores ranged from 6 to 30. Higher scores meant more symptoms for depression, anxiety, isolation and stress scales, but more resources for the resilience scale. We tested the questionnaire with five migrants before the main study. Two items were reworded based on their feedback about clarity.

In addition to these structured items, the questionnaire also included an open-ended section allowing participants to freely express their concerns and share their opinions in their own words. However, these narrative responses were not subjected to systematic qualitative analysis (coding, thematic analysis, inter-rater reliability) and therefore are not presented as findings. Informal patterns observed during interviews are mentioned in the Discussion solely as contextual background requiring future investigation

We acknowledge that reducing established instruments to 6-item scales enhances feasibility in challenging field conditions but limits direct comparability with validated full-length measures. While Cronbach's alpha coefficients (0.75-0.85, Table 2) indicate acceptable internal consistency for exploratory research, formal cultural adaptation and validation in North African migrant populations remain needed. Future research should employ fully validated, culturally adapted instruments to enable robust prevalence estimation and cross-cultural comparison.

Statistical analysis

Data entry and analysis were carried out using SPSS. Our analytic strategy combined pre-specified examinations (social isolation- depression relationship, gender differences) with emergent exploratory analyses (legal status, religious coping) that arose from patterns observed during fieldwork. While this approach lacks the rigor of pre-registered confirmatory designs, it enables comprehensive descriptive characterization in a population where baseline quantitative data are virtually nonexistent.

We ran descriptive analyses to examine frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations for the main variables. We checked whether our data followed normal distributions using Shapiro-Wilk tests and by looking at histograms and Q-Q plots.

Most of our composite scores were normally distributed. Social isolation scores showed a slight departure from normality (p = 0.03), and specific stress scores were borderline (p = 0.05), but these deviations were minor enough that we could still use parametric tests without concerns about validity.

We used Pearson correlations to examine relationships between continuous variables. Gender comparisons relied on independent samples t-tests with Cohen's d for effect sizes. To look at differences by length of residence, we ran one-way ANOVA with three groups: less than 12 months, 12-36 months, and over 36 months. We set statistical significance at p < 0.05 and interpreted effect sizes using Cohen's conventions (small = 0.2, medium = 0.5, large = 0.8). We checked test assumptions before running any analyses.

We employed univariate ANOVAs for subgroup comparisons rather than multivariate approaches because our primary aim was descriptive characterization—documenting whether mean symptom levels differed across demographic groups—rather than predictive modeling of intercorrelated outcomes. While this approach limits our ability to account for shared variance among mental health dimensions and increases the risk of Type I error with multiple tests, it provides transparent, domain-specific effect estimates appropriate for an exploratory descriptive study. We set statistical significance at p < 0.05 without adjustment for multiple comparisons, recognizing this as a limitation. Future confirmatory research should employ integrated multivariate frameworks to simultaneously model interdependencies among psychological outcomes while controlling for covariates. Finally, we also conducted k-means clustering to identify groups of participants with similar symptom-resource configurations.

Results

Sociodemographic and migration characteristics

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of our 98 participants. The sample was predominantly young men (mean age 26.7 years), with irregular status being the most common situation (58.2%). The most frequent countries of origin were Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea and Mali. This pattern reflects both the diversity of sub-Saharan migration to Tunisia and the administrative precarity that characterises many migrants' experiences.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and migration characteristics (N = 98)

|

Variable |

Category |

n |

% |

|

Age (years) |

Mean ± SD |

26.7 ± 6.9 |

– |

|

Gender |

Male |

52 |

53.1 |

|

Female |

46 |

46.9 |

|

|

Legal status |

Regular |

27 |

27.6 |

|

Irregular |

57 |

58.2 |

|

|

In process |

14 |

14.3 |

|

|

Country of origin |

Côte d'Ivoire |

23 |

23.5 |

|

Guinea |

18 |

18.4 |

|

|

Mali |

15 |

15.3 |

|

|

Cameroon |

14 |

14.3 |

|

|

Senegal |

12 |

12.2 |

|

|

DR Congo |

11 |

11.2 |

|

|

Others |

5 |

5.1 |

|

|

Length of stay |

Mean ± SD (months) |

23.8 ± 13.5 |

– |

Psychometric reliability of instruments

We checked internal consistency using Cronbach's alpha coefficients. All scales showed good reliability, which confirmed our measurement approach worked well (Table 2 has the details).

Table 2 Internal consistency of the scales (Cronbach’s alpha, N = 98)

|

Scale |

Number of items |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Interpretation |

|

Depressive symptoms |

6 |

0.83 |

Good |

|

Anxiety symptoms |

6 |

0.79 |

Acceptable |

|

Social isolation |

6 |

0.85 |

Good |

|

Acculturative stress |

6 |

0.77 |

Acceptable |

|

Specific stressors |

6 |

0.75 |

Acceptable |

|

Social resources |

6 |

0.81 |

Good |

Psychosocial scores overview

The main descriptive results appear in Table 3. Across all three dimensions—depression (M = 17.6, SD = 3.8), anxiety (M = 18.4, SD = 4.0), and social isolation (M = 17.9, SD = 3.9)—participants reported mean scores above the theoretical scale midpoint of 15 on the 6-30 range. These results reflect self-reported symptom endorsement within this sample. Without validated clinical cut-offs, normative comparison data, or diagnostic thresholds, we cannot determine what proportion of participants would meet criteria for clinical disorders or whether these scores are elevated relative to general population norms.

Table 3 Descriptive scores for psychosocial dimension

|

Dimension |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

SD |

Median |

Q1–Q3 |

|

Depression |

11 |

26 |

17.6 |

3.8 |

18 |

15–20 |

|

Anxiety |

12 |

28 |

18.4 |

4.0 |

18 |

16–21 |

|

Social isolation |

10 |

26 |

17.9 |

3.9 |

18 |

15–21 |

|

Acculturative stress |

10 |

24 |

17.5 |

3.2 |

17 |

15–20 |

|

Social resources |

8 |

24 |

17.2 |

3.5 |

17 |

15–20 |

Social isolation and depression link

Pearson correlation analysis revealed a moderate and statistically significant association between social isolation and depressive symptoms (r = 0.47, p < 0.001; Table 4). This relationship represented the strongest and most theoretically central bivariate association observed among the psychosocial variables examined.

Other bivariate associations between psychological dimensions were examined but showed weaker or inconsistent patterns and are therefore not detailed here.

Table 4 Pearson’s correlation between social isolation and depressive symptoms (N = 98)

|

Variable |

Social isolation |

Depression |

|

Social isolation |

1 |

0.47** |

|

Depressive symptoms |

0.47** |

1 |

Note: p < 0.001

Gender differences

Men had significantly higher depression scores than women. Other dimensions showed no notable gender differences (Table 5). Anxiety symptoms appeared relatively homogeneous across subgroups, showing no significant variation by gender, length of residence, or legal status. This pattern suggests that anxiety may represent a diffuse and broadly shared experience in this population rather than a dimension structured by specific sociodemographic or migratory factors.

Table 5 Mean scores by gender

|

Dimension |

Men (n = 52) |

Women (n = 46) |

p-value |

Cohen’s d |

|

Depression |

18.4 (3.9) |

16.8 (3.6) |

0.018 |

0.46 |

|

Anxiety |

18.4 (4.2) |

18.3 (3.8) |

0.91 |

0.02 |

|

Social isolation |

18.1 (3.8) |

17.7 (4.0) |

0.65 |

0.10 |

|

Acculturative stress |

17.8 (3.4) |

17.2 (3.1) |

0.42 |

0.18 |

|

Social resources |

17.1 (3.7) |

17.2 (3.4) |

0.93 |

0.02 |

Length of residence effects

Grouping participants by time in Tunisia revealed no significant differences in mental health scores. Psychological distress and resources remained stable regardless of how long people had been in the country (full results in Table 6).

Table 6 Mean scores by length of stay

|

Dimension |

< 12 m (n = 18) |

12–36 m (n = 52) |

> 36 m (n = 28) |

F |

p-value |

|

Depression |

17.3 (3.9) |

17.9 (3.7) |

17.6 (3.8) |

0.20 |

0.82 |

|

Anxiety |

18.1 (3.9) |

18.7 (4.0) |

18.2 (3.9) |

0.23 |

0.79 |

|

Social isolation |

17.8 (4.0) |

18.0 (4.0) |

17.9 (3.8) |

0.02 |

0.98 |

|

Acculturative stress |

17.4 (3.3) |

17.6 (3.4) |

17.5 (3.0) |

0.02 |

0.98 |

|

Social resources |

17.0 (3.6) |

17.2 (3.4) |

17.5 (3.6) |

0.15 |

0.86 |

Legal status and symptom levels

Legal status (regular, irregular, in process) was not associated with significant variations in depression, anxiety, isolation or psychosocial resources. We observed only non-significant trends (Table 7).

Table 7 Mean scores by legal status

|

Dimension |

Regular (n = 27) |

Irregular (n = 57) |

Pending (n = 14) |

F |

p-value |

|

Depression |

17.1 (3.6) |

17.8 (3.8) |

17.6 (3.8) |

0.25 |

0.78 |

|

Anxiety |

18.2 (3.8) |

18.4 (4.0) |

18.5 (3.8) |

0.04 |

0.96 |

|

Social isolation |

17.4 (3.7) |

18.0 (3.9) |

17.8 (4.0) |

0.17 |

0.84 |

|

Acculturative stress |

17.2 (3.4) |

17.6 (3.3) |

17.5 (3.2) |

0.06 |

0.94 |

|

Social resources |

17.1 (3.5) |

17.3 (3.5) |

17.4 (3.6) |

0.03 |

0.97 |

Symptom-resource profiles through clustering

We conducted k-means clustering to identify groups of participants with similar symptom-resource configurations. We compared solutions with 2 to 6 clusters and selected the 4-cluster solution based on: (1) adequate cluster sizes (all n > 20), (2) distinct and interpretable profiles, and (3) maximisation of between-cluster variance while maintaining within-cluster homogeneity. K-means partitioning used standardised scores across all six psychological dimensions (depression, anxiety, social isolation, acculturative stress, specific stressors, and psychosocial resources). ANOVA analyses confirmed significant between-cluster differences across all dimensions (all p < .001).

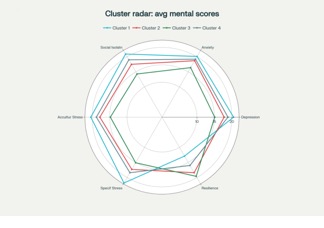

Cluster analysis identified four distinct symptom–resource profiles characterised by specific combinations of psychological symptoms and perceived psychosocial resources (Table 8). This segmentation illustrates the heterogeneity of mental health experiences within the sample. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of these profiles.

Table 8 Symptom–resource profiles identified through cluster analysis (N = 98)

|

Cluster |

n |

Depression |

Anxiety |

Isolation |

Accult. Stress |

Specific Stress |

Resilience |

Clinical profile |

|

1 |

24 |

20.5 (2.1) |

20.1 (2.3) |

20.9 (1.8) |

20.4 (1.9) |

21.8 (2.0) |

12.9 (2.4) |

Severe distress, low resilience |

|

2 |

26 |

17.8 (2.0) |

18.7 (2.1) |

17.5 (2.2) |

17.8 (1.8) |

17.3 (2.3) |

18.4 (1.7) |

Moderate distress, good resources |

|

3 |

27 |

15.1 (2.4) |

16.4 (2.0) |

14.3 (2.1) |

14.8 (2.2) |

15.1 (2.0) |

19.6 (1.9) |

Low symptoms, high resilience |

|

4 |

21 |

18.9 (2.2) |

19.2 (2.0) |

19.0 (2.3) |

18.8 (2.1) |

18.4 (2.4) |

16.0 (2.2) |

High distress, modest resources |

Note: Values are presented as means (standard deviation). Possible scores: 6-30 for each dimension. ANOVA analyses confirmed significant differences between clusters across all dimensions (p < 0.001)**, supporting the robustness of the clustering solution.

The four clusters point to meaningful heterogeneity in the ways distress and resilience are configured in this population. Cluster 1 (n = 24) is characterised by consistently high scores across all symptom dimensions together with the lowest resilience levels, suggesting marked psychological suffering in the context of limited coping capacity. In contrast, Cluster 3 (n = 27) shows the lowest levels of depressive, anxious and isolation symptoms, combined with the highest resilience scores, and can be viewed as a relatively protected profile with strong adaptive resources. Cluster 2 (n = 26) occupies an intermediate position, with moderate symptom levels that appear buffered by relatively well-preserved psychosocial resources. Cluster 4 (n = 21) also presents elevated symptom levels, albeit somewhat lower than Cluster 1, alongside intermediate resilience scores, pointing to high distress that is only partially offset by modest coping capacity.

Figure 1 visually reinforces these patterns, with contrasts between clusters most apparent for depression, anxiety, social isolation and resilience, while acculturative and specific stress also distinguish groups, though somewhat less sharply. Cluster sizes were relatively balanced, ranging from 21 to 27 participants. In light of the exploratory design and modest sample size, these profiles should nevertheless be interpreted with caution and understood as descriptive symptom–resource configurations rather than clinically diagnostic categories, pending replication in larger samples to examine their stability and potential clinical utility.

Figure 1 Radar of Average Psychological Scores by Cluster (n=4)

Discussion

This study provides new quantitative evidence on the mental health challenges facing Sub-Saharan African migrants in Tunisia, a population that remains severely understudied. Mean symptom scores across all dimensions fell above the theoretical scale midpoint, suggesting participants endorsed psychological distress symptoms at levels that, while not clinically validated, indicate meaningful symptom burden. We emphasize that without validated diagnostic instruments, established cut-offs, or normative reference data, we cannot estimate clinical prevalence rates or determine how these scores compare to general population norms. Future research with standardized measures (e.g., PHQ-9 ≥10 for moderate depression) is needed to establish true prevalence estimates in this population. These patterns align with risks well outlined by the biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977; Silove et al., 2017) and many studies linking migration, precarity, and mental health (Hajak et al., 2021; Martin, 2023).

Social isolation and mental health: a confirmed link

The moderate positive correlation between social isolation and depressive symptoms (r = 0.47, p < 0.001) confirms what research has long pointed to: isolation as a major factor in mental distress among migrants (Bridger & Evans, 2019; Lim et al., 2022; Hajak et al., 2021).Social isolation here means both lack of contact (objective isolation) and feelings of loneliness or exclusion (subjective isolation). Such isolation harms integration and wellbeing (Torabian, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2024).

In Tunisia, though, some cultural and community factors seem to soften these effects. Transnational networks, the use of technology, and solidarity within the diaspora appear to provide resilience resources. These might be overlooked by standard Western measures and invites us to rethink how social isolation is measured and adapt tools to African realities, which are more collective and community-based than typical Western scales assume (Berkman & Glass, 2000).

Gender specificity: unexpected male vulnerability

One notable finding of this study is the unexpectedly higher vulnerability of men to depressive symptoms. This contrasts with most epidemiological research, which generally reports higher prevalence among women (Hollander et al., 2011). In precarious migration contexts, however, similar patterns have been observed (Martin, 2023; Silove et al., 2017). Several mechanisms may account for this trend. Traditional masculine roles—particularly those emphasizing economic provision and social responsibility—are profoundly challenged by the realities of exile, administrative obstacles, and chronic job insecurity. These disruptions can trigger identity conflict and moral suffering (Hollander et al., 2011; Hajak et al., 2021). Moreover, men often express distress less openly and are less likely to seek psychological or social support, which tends to exacerbate depressive symptoms (Touzel et al., 2025). In contrast, migrant women frequently rely on stronger informal networks and show greater willingness to seek help, which may serve as protective resources. Together, these observations underscore the importance of gender-sensitive clinical approaches that explicitly address male-specific vulnerabilities in migratory situations (Silove et al., 2017).

During fieldwork, many participants informally expressed viewing Tunisia as a temporary transit point rather than a destination. Although no systematic qualitative analysis of these narratives was undertaken, this sense of impermanence might help explain why psychological distress persists regardless of length of stay (Table 6). Migrants who maintain a forward-looking “waiting for Europe” mindset may invest less in local integration, thus reinforcing social isolation. This hypothesis remains speculative and calls for dedicated, qualitative investigation using rigorous thematic analysis.

Finally, numerous participants spontaneously mentioned faith and spirituality when discussing sources of strength. While our quantitative indicator of psychosocial resources included a single item on religious coping, this measure is insufficient to elucidate the mechanisms involved. Future mixed-methods research should explicitly examine how religious practices, communal worship, and spiritual meaning-making contribute to resilience within migrant populations.

Effects of length of stay: persistent vulnerability

Our analysis revealed no significant differences in mental health scores across duration-of-residence groups (< 12 months, 12–36 months, > 36 months), suggesting that time spent in Tunisia alone does not substantially affect psychological wellbeing. A secondary analysis using exact months as a continuous variable confirmed this overall stability, with one exception: a slight but significant linear decrease in stress over time (coef. = −0.0486; p = 0.046). This modest reduction may indicate gradual adaptation to practical challenges such as housing, mobility within the city, or informal healthcare use. However, this limited improvement does not extend to broader indicators of mental health.

Within Tunisia’s migration landscape, this pattern is meaningful. The absence of improvement over time likely reflects the country’s status as a transit space for many migrants—a temporary waypoint rather than a permanent destination offering genuine opportunities for social anchoring. This intermediary condition feeds uncertainty and instability, preventing sustained integration. The lack of legal status for most participants compounds this vulnerability.

From a clinical perspective, the persistence of psychological distress suggests that suffering is not confined to an initial “arrival shock.” It endures because of ongoing structural constraints: restricted integration prospects, everyday discrimination, limited resource access, and reliance on short-term survival strategies. In this context, time alone does not heal. Without targeted interventions and improvements in living conditions, mental health trajectories risk remaining static—or worsening over time.

Heterogeneity of psychological profiles

Our cluster analysis underscores how varied the balance between symptoms and psychosocial resources can be in this group. Beyond the most extreme profiles, the intermediate configurations show that levels of distress and available resources do not always move together in a simple or predictable way. This insight matters for practice: a single intervention model is unlikely to meet the needs of everyone, and support has to be shaped around different constellations of vulnerability and strength. In some cases, migrants may need more intensive psychological care coupled with concrete material assistance; in others, the priority may be to reinforce and mobilise coping strategies that are present but not yet sufficient. Given the exploratory design and modest sample size, these patterns should still be viewed as provisional, and larger studies will be needed before they can guide clinical decisions with confidence.

Clinical and policy implications

These results invite a rethinking of migrant mental health policies in Tunisia and similar contexts. Services need to be explicitly gender- and culture-sensitive, paying attention to male-specific experiences of distress and to culturally shaped expressions of suffering (Hajak et al., 2021). Interventions should also take seriously the complexity of support sources among African migrants, including transnational ties, diaspora solidarity, and religious or community-based practices (Nguyen et al., 2024). In this study, participants most often identified diaspora networks, faith-based support, and informal mutual aid as key psychosocial resources, but the measure used focused on perceived availability rather than actual use. Some migrants may recognise potential sources of help without turning to them, for example because of mistrust, stigma, or practical barriers. Addressing structural determinants of mental distress therefore remains essential, particularly legal precarity, discrimination, and obstacles to employment and mental healthcare (Côté-Olijnyk et al., 2024). In this perspective, community strategies that strengthen migrant associations, trusted intermediaries, and collective support rituals appear crucial to counter social isolation and, more broadly, to reinforce informal social networks and community-based structures that can foster resilience and reduce psychological vulnerability.

Limitations of the study

This study stands out for its use of standardised measurement tools combined with a rigorous statistical approach in a context that is both sensitive and difficult to access. The recruitment strategy, spanning diverse neighbourhoods and participant profiles, allowed for a richer overview of the realities faced by sub-Saharan African migrants living in Greater Tunis. By integrating multiple dimensions of mental health—depression, anxiety, social isolation, acculturative stress and psychosocial resources—the analysis captures the complexity of their psychosocial condition in a nuanced and realistic way.

However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. Interview conditions varied by recruitment location, potentially introducing contextual variability. At the same time, this pragmatic approach enabled access to a population that would likely have been unreachable through more controlled procedures. Our use of multiple independent ANOVAs rather than multivariate methods limits inference, as it does not account for intercorrelations among outcomes or control for multiple testing. While appropriate for initial descriptive exploration, this strategy does not provide the level of rigor required for robust predictive or explanatory modelling. The cross-sectional design also precludes establishing any causal relationships between the variables studied. Measures of social isolation, although psychometrically sound, were developed in Western contexts and may not fully capture the cultural specificities of African migrant communities, where collective and community ties can take forms that fall outside conventional scales. The exclusive reliance on self-reported questionnaires may have introduced social desirability bias, potentially stronger among participants with irregular migration status. Finally, because data collection took place solely in the Greater Tunis area, the results cannot be generalised to all migrant populations in Tunisia, particularly those in other regions facing different local challenges.

The most significant limitation remains our inability to estimate clinical prevalence or determine diagnostic caseness. Without validated cut-off scores, we cannot state what proportion of participants would meet diagnostic criteria for depression, anxiety or other disorders. Mean scores above the scale midpoint suggest a substantial symptom burden but do not constitute epidemiological prevalence data. Claims about “high” or “elevated” scores are therefore relative only to theoretical scale ranges, not to clinical thresholds or population norms. Readers should interpret our findings as a descriptive characterisation of symptom endorsement patterns rather than as clinical prevalence estimates. Future research should employ validated instruments with established diagnostic thresholds (e.g. PHQ-9 ≥ 10, GAD-7 ≥ 10) to enable rigorous prevalence estimation and clinically meaningful interpretation.

Research perspectives

Several avenues could deepen understanding of migrant mental health in North Africa. Longitudinal designs would make it possible to follow trajectories of adaptation over time and to compare situations of transit or exile with more settled forms of migration. Mixed‑method approaches, combining quantitative measurement with qualitative exploration of lived experience, informal support networks and the meaning attributed to migration, would offer a more complete picture. Particular attention should be given to culturally adapting and validating instruments that capture forms of isolation, resilience and collective resources specific to African societies. There is also a need for intervention research evaluating culturally sensitive, community‑based and gender‑responsive clinical models. Comparative studies in different national settings could help distinguish what is specific to Tunisia from patterns driven by broader regional or global dynamics of migration and mental health.

Our study objectives were necessarily constrained by sample size and the exploratory nature of the design; more ambitious questions, such as modelling intersecting relationships between determinants, would require multivariate approaches with larger samples. Going forward, pre‑registered, hypothesis‑driven studies with clearly specified analytic plans would allow more robust, confirmatory inferences and complement the descriptive insights generated here by testing specific mechanistic pathways.

From an intervention perspective, future work should prioritise community‑based programmes that build on peer and family support networks, religious and spiritual resources, and adaptive coping strategies such as cognitive reframing and positive thinking, which are often linked to resilience in refugee populations (Paudyal et al., 2023). Pilot trials of culturally adapted group interventions delivered through diaspora organisations would be particularly informative, as would studies examining how transit‑migration contexts shape the effectiveness and acceptability of such programmes (Siviş et al., 2024; Witt, 2025). Methodologically, there is a strong case for moving beyond univariate descriptive comparisons towards multivariate frameworks—such as MANCOVA, multivariate regression or structural equation modelling—that can model interdependencies between depression, anxiety, isolation and acculturative stress while adjusting for demographic and contextual covariates. Such approaches would allow a more nuanced understanding of how risk and protective factors jointly shape mental health profiles in this population.

Conclusions

This study offers an initial quantitative portrait of mental health among sub-Saharan African migrants in Greater Tunis, a population that has received limited empirical attention. Participants reported symptom levels above theoretical scale midpoints across depression, anxiety, social isolation and acculturative stress, indicating a substantial psychological burden even if clinical prevalence cannot be established without validated diagnostic instruments. Three findings warrant particular attention: a significant association between social isolation and depressive symptoms, unexpectedly higher depression scores among men compared to women, and the identification of four distinct symptom–resource profiles that reveal considerable heterogeneity within this population.

What stands out most is the persistence of distress over time. No significant differences in depression, anxiety or social isolation emerged between recent arrivals and those who had been in Tunisia for more than three years, and only migration-specific stressors showed a modest decline. Taken together, these patterns suggest that psychological suffering is rooted less in short-term adjustment difficulties than in chronic structural conditions. In a setting where Tunisia functions primarily as a transit space rather than a stable destination, legal precarity, discrimination and restricted access to employment and healthcare tend to remain constant regardless of length of residence.

The implications extend beyond clinical practice. Mental health services need to be culturally grounded, gender-sensitive and accessible irrespective of legal status, yet psychological care on its own cannot address distress produced by structural exclusion. Pathways to legal regularisation, protection from discrimination and the integration of mental health considerations into migration policy are essential if responses are to target underlying causes rather than symptoms alone.

Community structures play a critical role in this landscape. The cluster analysis suggested that migrants who perceive access to psychosocial resources report markedly lower levels of distress than those who lack such support. Diaspora associations, faith communities and informal mutual aid networks already provide much of the practical and emotional assistance available to migrants, often compensating for gaps in formal services. Strengthening these community-based systems should therefore be seen as a core intervention strategy rather than an optional supplement.

This research provides empirical grounding for further work but also highlights important gaps. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, and the abbreviated scales used here, although reliable, limit direct comparison with standard instruments and do not permit robust prevalence estimates. The exploratory analyses reported should be followed by hypothesis-driven, longitudinal and intervention-focused studies that use culturally validated tools, test community-based approaches in transit contexts and examine how structural and psychosocial factors jointly shape mental health trajectories.

Migration flows through North Africa continue to intensify, and responses from receiving countries will determine whether borders can be managed while respecting human dignity. The psychological distress documented in this study is consistent with the view that at least part of this distress is preventable and linked to modifiable structural conditions, rather than an inevitable consequence of migration itself. Addressing these patterns will require political commitment, coordination across health, social and legal sectors, and sustained investment in interventions informed by both rigorous evidence and the knowledge of migrant communities.

Author Contributions

The author conceived and designed the study, carried out all stages of data collection in the field, performed the statistical analyses, and interpreted the results. The author also drafted and revised the manuscript in its entirety, taking full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work.

Use of AI Technology

The author used AI-based tools to support language refinement, verify the coherence of interpretations related to statistical models, generate summaries of selected academic references, and assist in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Ethics Statement

The study involved voluntary and anonymous participation of individuals responding to a mental health questionnaire. All participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in the study. Anonymity and confidentiality of personal information were strictly guaranteed, and participation was entirely voluntary. No financial or material compensation was provided. According to the applicable national and institutional guidelines, this study did not require formal approval from an Ethics Review Board. Therefore, no ethical approval number, issuing institution, or date is applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymised dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16898336

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The author warmly thanks all participants for their trust and openness, as well as the local organisations and migrant community leaders whose support helped make recruitment possible. Particular appreciation is extended to the cultural mediators and field assistants whose involvement ensured that data collection was conducted with respect, cultural sensitivity, and care.

References

Ben Abid, I., Ouali, U., Ben Abdelhafidh, L., & Peterson, C. E. (2023). Knowledge, attitudes and mental health of sub-Saharan African migrants living in Tunisia during COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychology, Advance online publication, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04607-z

Berkman, L. F., & Glass, T. (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In L. F. Berkman & I. Kawachi (Eds.), Social Epidemiology (pp. 137–173). Oxford University Press.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Bridger, O., & Evans, R. (2019). Tackling loneliness and social isolation in Reading (Research Report). Participation Lab, University of Reading. https://images.reading.gov.uk/2020/10/Bridger-and-Evans-2019-Tackling-Loneliness-in-Reading-report.pdf.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Côté-Olijnyk, M., Perry, J. C., Paré, M. È., & Kronick, R. (2024). The mental health of migrants living in limbo: A mixed-methods systematic review with meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 337, 115931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2024.115931

Devillanova, C., Franco, C., & Spada, A. (2024). Downgraded dreams: Labor market outcomes and mental health in undocumented migration. SSM - Population Health, 26, 101652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2024.101652

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Fadhlia, T. N., Doosje, B., & Sauter, D. A. (2025). The socio-ecological factors associated with mental health problems and resilience in refugees: A systematic scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 26(3), 598–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380241284594

Gargano, M. C., Ajduković, D., & Vukčević Marković, M. (2022). Mental health in the transit context: Evidence from 10 countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063476

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. (2024). Tunisia: Irregular migration reaches unprecedented levels. GI-TOC. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Tunisia-Irregular-migration-reaches-inprecedented-levels-GI-TOC-August-2024.pdf

Hajak, V. L., Sardana, S., Verdeli, H., & Grimm, S. (2021). A systematic review of factors affecting mental health and well-being of asylum seekers and refugees in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 643704. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643704

Hansen, T., Nes, R. B., Hynek, K., et al. (2024). Tackling social disconnection: An umbrella review of RCT-based interventions targeting social isolation and loneliness. BMC Public Health, 24, 1917. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19396-8

Hollander, A.-C., et al. (2011). Gender-related mental health differences between refugees and non-refugee immigrants: A cross-sectional register-based study. BMC Public Health, 11, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-180

Lim, M., Van Hulst, A., Pisanu, S., & Merry, L. (2022). Social isolation, loneliness and health: A descriptive study of the experiences of migrant mothers with young children (0–5 years old) at La Maison Bleue. Frontiers in Global Women's Health, 3, 823632. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.823632

Lumley, M., Katsikitis, M., & Statham, D. (2018). Depression, anxiety, and acculturative stress among resettled Bhutanese refugees in Australia. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(8), 1269-1282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118786458

Martin, F. (2023). The mental health of adult irregular migrants to Europe: A systematic review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 25(2), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-022-01379-9

Nguyen, T. P., Al Asaad, M., Sena, M., & Slewa-Younan, S. (2024). Loneliness and social isolation amongst refugees resettled in high-income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 360, 117340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117340

Nowak, A. C., Nutsch, N., Brake, T. M., Gehrlein, L. M., & Razum, O. (2023). Associations between postmigration living situation and symptoms of common mental disorders in adult refugees in Europe: updating systematic review from 2015 onwards. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1289. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15931-1

Paudyal, P., Purkait, N., & Fey, J. (2023). Mental health resilience among refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health, 33 (Supplement_2), ckad160.1628. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckad160.1628

Roberts, A. (2023). The biopsychosocial model: Its use and abuse. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 26(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-023-10150-2

Silove, D., Ventevogel, P., & Rees, S. (2017). The contemporary refugee crisis: An overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20438

Siviş, S., Brändle, V. K., Eberl, J.-M., Wyatt, S., Braun, K., Metwally, I., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2024). Oscillating between hope and despair: Understanding migrants' reflections on ambivalence in 'transit'. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2024.2337196

Small Arms Survey. (2024). Security over people: Tunisia's immigration crisis – Situation update October 2024. Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies. https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/resource/security-over-people-tunisias-immigration-crisis

Torabian, D. (2019). Home and healing in the in-between: Migrant and refugee mental health in Tunisia (Independent Study Project No. 3055). SIT Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4082&context=isp_collection

Touzel, V., Reifegerste, D., Bozorgmehr, K., & Biddle, L. (2025). Impact of social isolation on mental health changes by socio-economic status: A moderated mediation analysis among non-migrant, migrant, and refugee subpopulations in Germany, 2016–2020. SSM - Population Health, 31, 101822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2025.101822

UNHCR. (2024). Tunisia: Operational update June–August 2024. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. https://reliefweb.int/report/tunisia/unhcr-tunisia-operational-update-june-august-2024

Yun, S., Ahmed, S. R., Hauson, A. O., & Al-Delaimy, W. K. (2021). The relationship between acculturative stress and postmigration mental health in Iraqi refugee women resettled in San Diego, California. Community mental health journal, 57(6), 1111-1120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00739-9

STROBE Statement—checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies

|

1 |

(a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract |

1 |

||

|

(b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found |

1 |

|||

|

2 |

Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported |

2 |

||

|

3 |

State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses |

2 |

||

|

4 |

Present key elements of study design early in the paper |

1&3 |

||

|

5 |

Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection |

3 |

||

|

Participants |

6 |

(a) Cohort study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants. Describe methods of follow-up Case-control study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of case ascertainment and control selection. Give the rationale for the choice of cases and controls Cross-sectional study—Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants |

3 |

|

|

(b) Cohort study—For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed Case-control study—For matched studies, give matching criteria and the number of controls per case |

Not applicable |

|||

|

7 |

Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable |

4 |

||

|

8* |

For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group |

4 |

||

|

9 |

Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias |

3 & 5 |

||

|

10 |

Explain how the study size was arrived at |

3 |

||

|

11 |

Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why |

4&5 |

||

|

Statistical methods |

12 |

(a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding |

5 |

|

|

(b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions |

5 |

|||

|

(c) Explain how missing data were addressed |

3 |

|||

|

(d) Cohort study—If applicable, explain how loss to follow-up was addressed Case-control study—If applicable, explain how matching of cases and controls was addressed Cross-sectional study—If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy |

3 |

|||

|

(e) Describe any sensitivity analyses |

Not applicable |

|||

|

Results |

||||

|

13* |

(a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—eg numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analysed |

Nearly 300 individuals were approached, but only 98 completed the interview. |

||

|

(b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage |

Several individuals were unavailable without providing a specific reason. |

|||

|

no flow diagram was used in this study. |

||||

|

14* |

(a) Give characteristics of study participants (eg demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders |

Sociodemographic and migratory characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1, page 10 |

||

|

(b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest |

No missing data were observed for key variables |

|||

|

(c) Cohort study—Summarise follow-up time (eg, average and total amount) |

Not applicable |

|||

|

15* |

Cohort study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time |

Not applicable |

||

|

Case-control study—Report numbers in each exposure category, or summary measures of exposure |

Not applicable |

|||

|

Cross-sectional study—Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures |

Outcome data are presented as summary measures (mean scores, standard deviations, medians) for key psychological dimensions: (pages 11 to 15 ) |

|||

|

16 |

(a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (eg, 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included |

No adjusted models were used |

||

|

(b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized |

Continuous variables were retained as scores |

|||

|

(c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period |

Not applicable |

|||

|

17 |

Report other analyses done—eg analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses |

Additional analyses included subgroup comparisons by gender, length of stay, and legal status (ANOVA), a K-means cluster analysis identifying foursymptom-resource profiles, and mediation/moderation tests between psychological dimensions. See Tables 5 to 8 |

||

|

18 |

Summarise key results with reference to study objectives |

A significant correlation was found between social isolation and depressive symptoms |

||

|

19 |

Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias |

Study limitations include selection bias resulting from the recruitment approach, as well as the absence of formal clinical data to validate psychological diagnoses. |

||

|

20 |

Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence |

The levels of psychological distress align with existing literature on vulnerable migrant populations. Observed correlations are interpreted as indicators of psychosocial vulnerability, without inferring causal relationships. |

||

|

21 |

Discuss the generalisability (external validity) of the study results |

The generalisability of findings is limited by the specific context of the study (Tunisia, vulnerable migrants) |

||

|

22 |

Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based |

This study received no external funding |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|